News Blog

Latest News From Our Volunteers in Nepal

VOLUNTEER COMMUNITY CARE CLINICS IN NEPAL

Nepal remains one of the poorest countries in the world and has been plagued with political unrest and military conflict for the past decade. In 2015, a pair of major earthquakes devastated this small and fragile country.

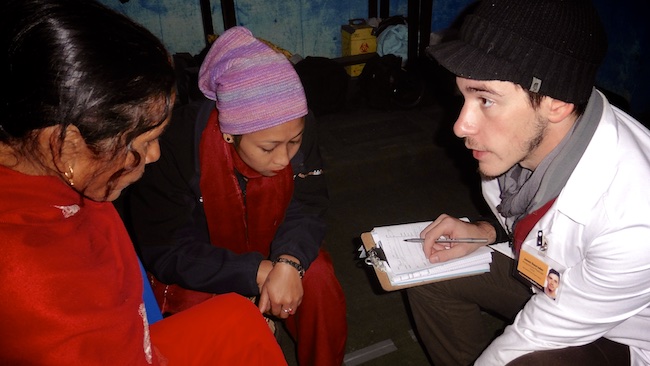

Since 2008, the Acupuncture Relief Project has provided over 300,000 treatments to patients living in rural villages outside of Kathmandu Nepal. Our efforts include the treatment of patients living without access to modern medical care as well as people suffering from extreme poverty, substance abuse and social disfranchisement.

Common conditions include musculoskeletal pain, digestive pain, hypertension, diabetes, stroke rehabilitation, uterine prolapse, asthma, and recovery from tuberculosis treatment, typhoid fever, and surgery.

FEATURED CASE STUDIES

Rheumatoid Arthritis +

35-year-old female presents with multiple bilateral joint pain beginning 18 months previously and had received a diagnosis of…

Autism Spectrum Disorder +

20-year-old male patient presents with decreased mental capacity, which his mother states has been present since birth. He…

Spinal Trauma Sequelae with Osteoarthritis of Right Knee +

60-year-old female presents with spinal trauma sequela consisting of constant mid- to high grade pain and restricted flexion…

Chronic Vomiting +

80-year-old male presents with vomiting 20 minutes after each meal for 2 years. At the time of initial…

COMPASSION CONNECT : DOCUMENTARY SERIES

Episode 1

Rural Primary Care

In the aftermath of the 2015 Gorkha Earthquake, this episode explores the challenges of providing basic medical access for people living in rural areas.

Episode 2

Integrated Medicine

Acupuncture Relief Project tackles complicated medical cases through accurate assessment and the cooperation of both governmental and non-governmental agencies.

Episode 3

Working With The Government

Cooperation with the local government yields a unique opportunities to establish a new integrated medicine outpost in Bajra Barahi, Makawanpur, Nepal.

Episode 4

Case Management

Complicated medical cases require extraordinary effort. This episode follows 4-year-old Sushmita in her battle with tuberculosis.

Episode 5

Sober Recovery

Drug and alcohol abuse is a constant issue in both rural and urban areas of Nepal. Local customs and few treatment facilities prove difficult obstacles.

Episode 6

The Interpreters

Interpreters help make a critical connection between patients and practitioners. This episode explores the people that make our medicine possible and what it takes to do the job.

Episode 7

Future Doctors of Nepal

This episode looks at the people and the process of creating a new generation of Nepali rural health providers.

Compassion Connects

2012 Pilot Episode

In this 2011, documentary, Film-maker Tristan Stoch successfully illustrates many of the complexities of providing primary medical care in a third world environment.

From Our Blog

- Details

- By Helena Nyssen

Here in Nepal, very little is convenient. Nothing is handed to you on a platter ( except our dinner, thanks Auntie). The modern world of convenience has not yet arrived to Bimphedi. Their is no internal plumbing in the houses, nor heating, nor appliances. There is wifi though? Bizarre.

Everything takes 10 times longer because of this; cleaning clothes, having a shower, making coffee, making food etc. And we live in luxury compared to most locals. We enjoy hot water, electricity, and wifi!

It is much more apparent and more emotional at clinic. At home when someone presents to my clinic, they have probably already seen a doctor, and had some scans or tests (depending on their condition). They may already be under the care of a specialist. They usually know what they have and have a pretty good idea of how they got it. For the most part, patients arrive with a clear cut medical diagnosis. (NB. I'm talking about the Australian system here, our national medical system is, thankfully, very good). If they don't already have a diagnosis, it's free/cheap to obtain one. I can simply say, 'Go consult your Doctor, then come back to see me' and I can be confident that it will be taken care of on the other end. After this has been done, it is my job to apply Chinese Medical thinking and methods to their health problem.

At home, lumps are scanned, biopsied, and removed. At home, digestive ulcers are viewed by endoscopic cameras, medicine is given, and dietary advice is understood. Alcoholics have access to the help they need. STIs are tested for and managed. Lower backs are x-rayed and orthopaedically tested. The list goes on.

In Nepal, this is not the reality. Patients will come to our clinic with the problem, and no information beyond that.

Like the lady with the grapefruit-sized lump on her inner right thigh. It hurts. It's been there for 5 years. Can you help?

Like the woman with sore breasts for 6 months. They hurt. There are lumps. What's wrong?

Like the man with the chronic leg infection. Sometimes is weeps pus, sometimes it doesn't.

The children with paralysis from high fevers that weren't treated.

The out of control diabetes and high blood pressure.

The huge number of alcoholics.

We are triage; It is our job to ask all the right questions. Get an accurate symptom picture. Know which diseases are indicated. Know which tests will confirm or rule out these diseases. Hope that when we send them to the local hospital, they will actually perform the tests, prescribe the right medication, and if we're really lucky, explain what's wrong to the patient. This is all only if the patient can even pay for it at all.

We are also medical counsellors; We explain what is wrong to the patients as the doctors never seem to. And give good advice, a crucial part of health care in my opinion. How can people care for themselves and their families when they are given no information and their illiteracy prevents them from accessing it themselves.

And, then of course, we are doctors ourselves, performing treatments and providing ongoing care.

So this is what was meant when we were told that we are now 'Primary Care Physicians'? Ouch

In this setting I am finding the need to step up in a huge way. My clinical knowledge, especially western medicine diagnoses and disease management has had to be expanded in a big way. Not a bad thing, certainly. Thank God for the team of practitioners around me and the Merck Manual app! I've learnt that the important thing is not to know everything, that is impossible. The important thing is to care, and be willing to try and figure it out.

I've never learned so much, in such a hands-on way, in such a short space of time. Thank you ARP, my team mates, and, everyone back home who helped get me here.

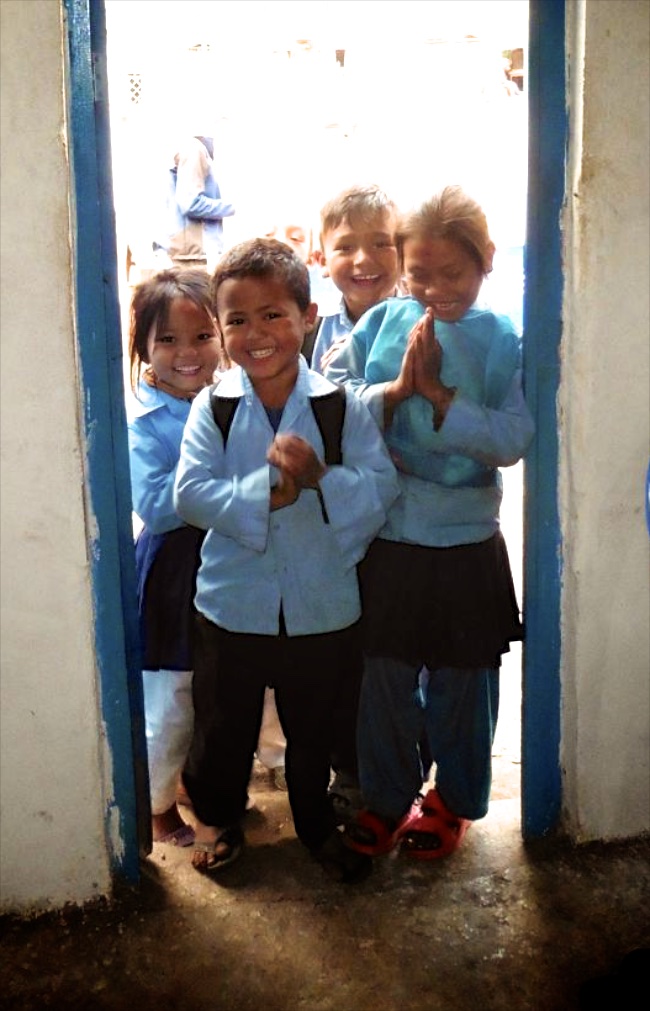

Most of all, thank you to my Nepali patients for being the sweetest and the absolute toughest teachers I have ever known.

Namaste,

Dr Leni

- Details

- By Rachael Haley

In my fourth week of volunteering at the Kogate Clinic, I hiked over an hour away to a town in the next valley called Ipa. Suman (my awesome translator) and I were on a mission to see an old patient of the project that has ALS (a degenerative neurological disease) and can no way make it to our clinic.

Bim is in his 80's. He can't walk and can only really manage to go from sitting to to lying by just falling backwards onto a well placed cushion. If he wants to sit back up he needs someone to lift him. He lives with his wife on the top of a hill overlooking Ipa valley. From the other side of the ridge you can see white capped Himalayan peaks across on the horizon. It is really quite picturesque, but because it's so remote walking to and from here can be quite difficult. The road there is very uneven and rocky; even a motorbike would have trouble with the steep climb.

We arrive at Bim's, passing the neighbouring house where a couple of grazing buffalo peeking up at us and a dog barking protecting his territory greet us. Bim is sitting on the porch of his little mud house looking a little blank and weary. His wife gets up to welcome us and asks if we'll be staying for lunch, which we politely decline. She herself is in her 70's, a tiny lady that has obviously worked hard her whole life. She stands so stooped over I can only imagine that having her husband immobile has given her more than her fair share of work each day.

This is my first experience visiting someone to do a remote treatment. I'm not even sure where to start. I ask how he's doing and we go straight to checking out his worrisome bed sores. After attending to these and educating his wife to keep them clean and dry, I proceed to cut his finger nails and gather more information about his general well being.

While he was still up for it, I gave him some electro-acupuncture to stimulate the muscles in his legs but he didn't last long before getting uncomfortable. Staying in one position for too long was Bim's biggest problem and his wife can barely manage to help lift him from sitting. I'm guessing without any extra help she must drag him across the mud house floor to his bed.

I chatted and demonstrated to Bim the importance of regularly moving the muscles in his feet and legs to preserve the limited movement and strength while helping his circulation. While I gave his wife an acupuncture treatment I kept checking to see if he was doing his exercises, which he found quite amusing.

Luckily, I had packed some herbal antibiotics which I prescribed partly for his bed sores and also more concerning was his burning and occasionally bloody urination. I was concerned he had a possible infection, prostate issues, or something more sinister, so I planned to further discuss with the team the logistics of getting him more care.

This really felt like a hopeless situation I was walking into, however, he has no other support; while his wife is doing everything she can. All I could do was the best on the spot healthcare I could provide while trying to make him smile and feel cared for. After spending just over an hour with the couple Suman and I made the trek back to Kogate in time for lunch. On the way Suman said 'I'm so happy today!' I asked him why and he replied 'we got to go for a nice walk and did you see the look on Bim's face when you said we'd be back next week?' I thought, yeah he's right, I feel happy too.

That moment really resonated with me as to why I'm really here.

I went back and visited Bim and his wife two more times before the camp ended. My last visit was bittersweet. I'd had a feeling this would be the case, so when Suman and I were walking to his house that day, I told Suman that I wanted to focus our visit on making Bim smile.

When we arrived Bim was lying on his porch with a tiny little black kitten by his side. The results from his urine test I had his son get while he was in Kathmandu were not great, but his discomfort when urinating had improved. The hardest part was seeing Bim's decline over the past two weeks. His feet were swelling more and now he couldn't wiggle his toes. We checked his sores, cut his finger nails and I decided only one acupuncture point was necessary as I gave him leg massage instead. We talked about the kitten in which his wife wasn't too keen on, but I could see he liked this cat. The cat had no name so I suggested Bim pick a name for the little kitten. He named her Kali (which means black in Nepali) and took much delight in me asking about Kali and bringing her over to say hello to him.

Once we'd finished his treatment and discussed getting another urine sample tested, Suman and Bim's son lifted him onto a straw mat in the sun. He laid on his side while I gave his wife an arm and shoulder massage in the sun. She looked so relaxed by the end of it. It was as if I'd lifted a weight from her shoulders. I was chatting with her and their son, until Suman pointed across to Bim where I saw him sleeping peacefully in the sun. He had only been sleeping one to two hours a night and in the past week had not been able to sleep during the day. This was a blessing. This was also the last time I saw Bim. And this is how I would hope he passes on when his time comes. Even though I knew I couldn't drastically change his situation I felt I gave him, his wife, and their son a little relief. --Rachael Haley

- Details

- By Jason Gauruder

“Are you a shaman, is there medicine in the needles?” is a question I hear a lot; which is not really that different than a steady stream of Americans asking if acupuncture really works, but here I don’t have to defend my profession using science terminology that people may remember from high school. I always decline being a shaman, but the question has me wondering if I should step out of the western mindset for a moment, since I am, after all, in Nepal.

The Acupuncture Relief Project is supposed to be a set schedule, you show up for six weeks, do the work, and conclude said scheduled events with empowering stories to tell your friends and family about life in the third world, but four weeks in I’m convinced that this short trip to a land I knew nothing about has become one of the greatest markers on my journey through life and as a practitioner. It has become a doorway that has opened me up to a flowing path of knowledge that has been cascading through time for millennia.

Being here is like stepping back in time. There’s our personal comforts of electricity and internet that keeps us connected with the other side of the planet thousands of miles away, but when we step past the front door a different reality comes into perspective. Not just one of rural Nepal, but of all rural places in which man inhabited across the globe up until the building of great city centers and the industrial revolution. The people can go as far as they can walk in a day, they must carry everything at once on their back (or heads), roads are traveled paths full of treacherous rocks, and their joints are put to the test on an hourly basis. Farm, family, and prayer is life. There isn’t much else, because when it takes you an entire morning to make breakfast or feed the animals that will eventually become dinner, there isn’t much time for anything else. Your neighbors will always be your neighbors. Your neighbors are probably distant cousins, and the town drunks are drunk because there’s no such thing as an –ism that explains an escape from the harshness of the world.

Then there’s me. Standing in the unique position of strolling down the street, settling down into clinic for the morning fighting my usual personal habits; which even on the other side of the world hold true to who I am: NOT A MORNING PERSON. Then slowly, but surely, magic happens. People tell me their stories of everyday life, their major issue that’s ailing them, and no more than the shamans of the past I pick my tools to either poke, burn, or send down their throat to subdue their suffering. At the end of the day my fellow practitioners and interpreters have become a clan. Like a family we speak our own language and do our respected duties to provide a service to the village. It’s in the moments after I’m done consuming the home grown and prepared dinner that I reflect on what happened on the day that passed. It all seems like a blur, because it seems like it can’t be described. I pull myself back to the moment when I touch my fingers to a patient’s wrist. Being in the moment while the spirits of past Chinese medicine scholars’ knowledge flow through me to try and explain what imbalance of the universe sits before me, speaking to me through a radial pulse. What is going on inside of them?

We’re spoiled with not having to grind and boil herbs for every person or prick them with animal bone needles, but for the most part I am living in the spirit of the greatest Chinese practitioners of the past. I am looking at people that live in the elements and are truly affected by the world around them. They are the microcosm that is showing me the macrocosm. The cold of winter after a damp rainy season is inside them. It’s in their joints, stagnating at the bottom of their pulse, and weighing on their mind. It’s up to me to see them as something more than tendonitis or gastritis. I have to see them in the world they live in, which is one where wood like tendons will break down easily if not nourished by smoothly flowing water, or that a spicy food diet is like scorching the earth over and over until the soil becomes dry and can no longer nourish the village. No electronic imaging means that lump is a big ball of damp requiring heat to unblock stasis. I have to look at them through the wisdom that is Chinese medicine and the realities it was born out of. Perhaps I am not a shaman, but I do wield a medicine that makes sense for their lives, because it was the medicine that was born out of the lives of generations of laboring villagers.

I get to escape the world that is studied in books and the perceived notion of modern scholars on what they think the classics mean. Formula and dosage dogma goes out the window when you have a limited amount of supplies. You use what you can get. You use what you have to the best of your ability and the presentation that is before you. Studying wind cold invasion in a text book or what the pulse should look like is nothing compared to meeting a woman who has been out in the cold all day working with a sparse amount of covering and didn’t have lunch heated in a slow cooker. It’s hard not to think cinnamon and ginger with hot porridge isn’t the best remedy no matter what the ratios are.

Like I said, it’s just a reminder of the journey. Here I am in a country that is culturally Hindu, I’m of European ancestry, and I’m learning about the true nature of Chinese medicine. I am uncovering the mystery of where this medicine came from and how it is so successful at treating the human condition. Being able to come here and have one epiphany after another certainly seems like magic to me. So the next time I get asked, “are you a shaman?” I may just have to respond, “with how all of this has worked out, I might just as well be.”

“The modest disposition begins with the recognition that there is no one method for solving problems. It’s important to rely on the quantitative and rational analysis. But that gives you part of the truth, not the whole….This is a different sort of knowledge [folk wisdom]. It comes from integrating and synthesizing diverse dynamics. It is produced over time, by an intelligence that is associational – observing closely, imagining loosely, comparing like to unlike and like to like to find harmonies and rhythms in the unfolding events. The modest person uses both methods and more besides. The modest person learns not to trust one paradigm. Most of what he knows accumulates through long & arduous process of wondering.” – David Brooks, The Social Animal

--Jason Gauruder

Our Mission

Acupuncture Relief Project, Inc. is a volunteer-based, 501(c)3 non-profit organization (Tax ID: 26-3335265). Our mission is to provide free medical support to those affected by poverty, conflict or disaster while offering an educationally meaningful experience to influence the professional development and personal growth of compassionate medical practitioners.