“Are you a shaman, is there medicine in the needles?” is a question I hear a lot; which is not really that different than a steady stream of Americans asking if acupuncture really works, but here I don’t have to defend my profession using science terminology that people may remember from high school. I always decline being a shaman, but the question has me wondering if I should step out of the western mindset for a moment, since I am, after all, in Nepal.

The Acupuncture Relief Project is supposed to be a set schedule, you show up for six weeks, do the work, and conclude said scheduled events with empowering stories to tell your friends and family about life in the third world, but four weeks in I’m convinced that this short trip to a land I knew nothing about has become one of the greatest markers on my journey through life and as a practitioner. It has become a doorway that has opened me up to a flowing path of knowledge that has been cascading through time for millennia.

Being here is like stepping back in time. There’s our personal comforts of electricity and internet that keeps us connected with the other side of the planet thousands of miles away, but when we step past the front door a different reality comes into perspective. Not just one of rural Nepal, but of all rural places in which man inhabited across the globe up until the building of great city centers and the industrial revolution. The people can go as far as they can walk in a day, they must carry everything at once on their back (or heads), roads are traveled paths full of treacherous rocks, and their joints are put to the test on an hourly basis. Farm, family, and prayer is life. There isn’t much else, because when it takes you an entire morning to make breakfast or feed the animals that will eventually become dinner, there isn’t much time for anything else. Your neighbors will always be your neighbors. Your neighbors are probably distant cousins, and the town drunks are drunk because there’s no such thing as an –ism that explains an escape from the harshness of the world.

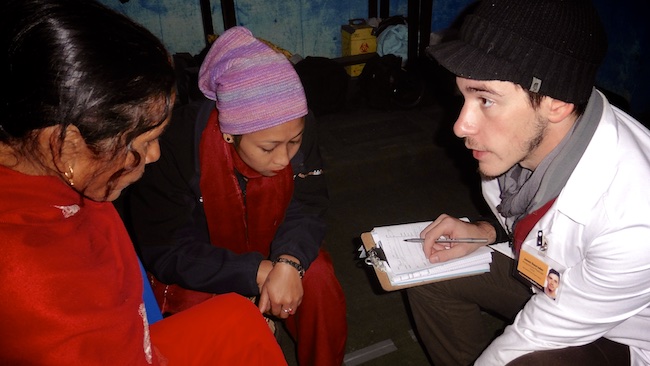

Then there’s me. Standing in the unique position of strolling down the street, settling down into clinic for the morning fighting my usual personal habits; which even on the other side of the world hold true to who I am: NOT A MORNING PERSON. Then slowly, but surely, magic happens. People tell me their stories of everyday life, their major issue that’s ailing them, and no more than the shamans of the past I pick my tools to either poke, burn, or send down their throat to subdue their suffering. At the end of the day my fellow practitioners and interpreters have become a clan. Like a family we speak our own language and do our respected duties to provide a service to the village. It’s in the moments after I’m done consuming the home grown and prepared dinner that I reflect on what happened on the day that passed. It all seems like a blur, because it seems like it can’t be described. I pull myself back to the moment when I touch my fingers to a patient’s wrist. Being in the moment while the spirits of past Chinese medicine scholars’ knowledge flow through me to try and explain what imbalance of the universe sits before me, speaking to me through a radial pulse. What is going on inside of them?

We’re spoiled with not having to grind and boil herbs for every person or prick them with animal bone needles, but for the most part I am living in the spirit of the greatest Chinese practitioners of the past. I am looking at people that live in the elements and are truly affected by the world around them. They are the microcosm that is showing me the macrocosm. The cold of winter after a damp rainy season is inside them. It’s in their joints, stagnating at the bottom of their pulse, and weighing on their mind. It’s up to me to see them as something more than tendonitis or gastritis. I have to see them in the world they live in, which is one where wood like tendons will break down easily if not nourished by smoothly flowing water, or that a spicy food diet is like scorching the earth over and over until the soil becomes dry and can no longer nourish the village. No electronic imaging means that lump is a big ball of damp requiring heat to unblock stasis. I have to look at them through the wisdom that is Chinese medicine and the realities it was born out of. Perhaps I am not a shaman, but I do wield a medicine that makes sense for their lives, because it was the medicine that was born out of the lives of generations of laboring villagers.

I get to escape the world that is studied in books and the perceived notion of modern scholars on what they think the classics mean. Formula and dosage dogma goes out the window when you have a limited amount of supplies. You use what you can get. You use what you have to the best of your ability and the presentation that is before you. Studying wind cold invasion in a text book or what the pulse should look like is nothing compared to meeting a woman who has been out in the cold all day working with a sparse amount of covering and didn’t have lunch heated in a slow cooker. It’s hard not to think cinnamon and ginger with hot porridge isn’t the best remedy no matter what the ratios are.

Like I said, it’s just a reminder of the journey. Here I am in a country that is culturally Hindu, I’m of European ancestry, and I’m learning about the true nature of Chinese medicine. I am uncovering the mystery of where this medicine came from and how it is so successful at treating the human condition. Being able to come here and have one epiphany after another certainly seems like magic to me. So the next time I get asked, “are you a shaman?” I may just have to respond, “with how all of this has worked out, I might just as well be.”

“The modest disposition begins with the recognition that there is no one method for solving problems. It’s important to rely on the quantitative and rational analysis. But that gives you part of the truth, not the whole….This is a different sort of knowledge [folk wisdom]. It comes from integrating and synthesizing diverse dynamics. It is produced over time, by an intelligence that is associational – observing closely, imagining loosely, comparing like to unlike and like to like to find harmonies and rhythms in the unfolding events. The modest person uses both methods and more besides. The modest person learns not to trust one paradigm. Most of what he knows accumulates through long & arduous process of wondering.” – David Brooks, The Social Animal

--Jason Gauruder