News Blog

Latest News From Our Volunteers in Nepal

VOLUNTEER COMMUNITY CARE CLINICS IN NEPAL

Nepal remains one of the poorest countries in the world and has been plagued with political unrest and military conflict for the past decade. In 2015, a pair of major earthquakes devastated this small and fragile country.

Since 2008, the Acupuncture Relief Project has provided over 300,000 treatments to patients living in rural villages outside of Kathmandu Nepal. Our efforts include the treatment of patients living without access to modern medical care as well as people suffering from extreme poverty, substance abuse and social disfranchisement.

Common conditions include musculoskeletal pain, digestive pain, hypertension, diabetes, stroke rehabilitation, uterine prolapse, asthma, and recovery from tuberculosis treatment, typhoid fever, and surgery.

FEATURED CASE STUDIES

Rheumatoid Arthritis +

35-year-old female presents with multiple bilateral joint pain beginning 18 months previously and had received a diagnosis of…

Autism Spectrum Disorder +

20-year-old male patient presents with decreased mental capacity, which his mother states has been present since birth. He…

Spinal Trauma Sequelae with Osteoarthritis of Right Knee +

60-year-old female presents with spinal trauma sequela consisting of constant mid- to high grade pain and restricted flexion…

Chronic Vomiting +

80-year-old male presents with vomiting 20 minutes after each meal for 2 years. At the time of initial…

COMPASSION CONNECT : DOCUMENTARY SERIES

Episode 1

Rural Primary Care

In the aftermath of the 2015 Gorkha Earthquake, this episode explores the challenges of providing basic medical access for people living in rural areas.

Episode 2

Integrated Medicine

Acupuncture Relief Project tackles complicated medical cases through accurate assessment and the cooperation of both governmental and non-governmental agencies.

Episode 3

Working With The Government

Cooperation with the local government yields a unique opportunities to establish a new integrated medicine outpost in Bajra Barahi, Makawanpur, Nepal.

Episode 4

Case Management

Complicated medical cases require extraordinary effort. This episode follows 4-year-old Sushmita in her battle with tuberculosis.

Episode 5

Sober Recovery

Drug and alcohol abuse is a constant issue in both rural and urban areas of Nepal. Local customs and few treatment facilities prove difficult obstacles.

Episode 6

The Interpreters

Interpreters help make a critical connection between patients and practitioners. This episode explores the people that make our medicine possible and what it takes to do the job.

Episode 7

Future Doctors of Nepal

This episode looks at the people and the process of creating a new generation of Nepali rural health providers.

Compassion Connects

2012 Pilot Episode

In this 2011, documentary, Film-maker Tristan Stoch successfully illustrates many of the complexities of providing primary medical care in a third world environment.

From Our Blog

- Details

- By Jeanne Mare Werle

Good Morning Nepal! It’s 5:30 a.m.

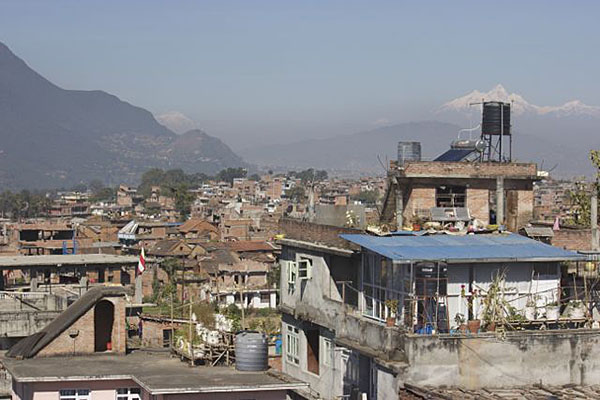

We at the Vajra Varihi Health Clinic are tossing our sleepy heads in bed while Monks twenty steps out the door are gonging, blowing gloriously long pipes and chanting from the deepest place in their bellies (a daily ritual known as puja: expressions of honor, worship, & devotional attention). Turning over again, the signal for dog singing of all shapes and sizes has begun. Children are walking to school taking no notice of the woman carrying plates loaded with red petaled flowers, candles and other mysterious herbs blessing their doorsteps. A procession of villagers begin to enter the inner courtyard of the Monastery and circle the Gompa clockwise, spin prayer wheels, and pass their best hopes out to the Universe. It’s almost 6:00 a.m.; We have been blessed with a lovely rooftop garden and I can’t resist witnessing the awakening of our village, Chapagaon, from this viewpoint, with a possible glimpse of the Himalayas. Ahh, there they are... and like everyone else on our team, I just can’t believe in one week I will walk amongst them!

Our workday is hours away, however I and my friend Diane have assigned ourselves the task of feeding a few stray dogs that call the inner courtyard their home. Off to the market for a dozen eggs and some milk, I am hoping to build their reserves for the Winter. The Monks share rice with them, so perhaps with the Mange cure we’ve been giving them (boiled lemon skins, from the renowned British Veterinarian Doctor Juliette Baircli de Levy), a few baths, and most importantly recognizing the light in their eyes, this year will be better, and maybe, just maybe, someone will carry on.

Black chickpeas and chapatis for breakfast and I am off to stock the treatment room. Once the doors open, the patients who have often been waiting there for hours, stream in with their shimmering eyes. Many walk for great distances or ride the dizzying microbus for hours, as if it were nothing, having heard from a friend or relative of great benefits received from the clinic. Two things I have noticed in my Nepali people are their extreme patience and their great ability to heal. They come frequently, which is how acupuncture shines, and they believe in the medicines of the Earth. Belief and intention - we talk about it all the time in acupuncture circles; The Nepali people live it.

Some many beautiful, cheerful days of patients sitting together sharing their stories, healing together. My favorite patient, Nuche is recovering from a stroke.

Each treatment another finger can move, the range of motion in his shoulder increases, his foot lifts a little higher. He smiles, he endures, his gratitude is heartbreaking. As he leaves my treatment room with his homemade walking stick and shyly one more time says Namaste, I understand how very lucky I am to be here, in this moment, with this extraordinary man. --Jeanne Mare Werle

- Details

- By Sarah Martin

Nepal is full of sacred sites – shrines, temples, and monasteries -some of which I’ve been graced with experiencing during my time off here. However, I’ve been reminded during my journey here that there is nothing more sacred than family – the family that gave what they could to help me get here despite relation, and my new family that has supported me through the challenging exhaustion that comes at us daily with treating as many patients as possible while sorting through the difficult conditions.

One of these challenging conditions belonged to a wonderful man with a family that displayed the ultimate commitment to their father’s wellbeing. Such a commitment in fact that in order to bring him to our clinic, his sons carried him literally on their back for two hours, then hired an ambulance to take him the rest of the three hours to get to our clinic doorstep. Upon hearing that his condition was far too severe to be fixed with one treatment, they rented a room in a local guesthouse to stay for the week to see how his condition would respond to treatment.

Upon assessment of his abilities and review of his CT scans and medical reports from M.D.s, we came to the conclusion that he was most likely suffering from an advanced aggressive form of Multiple Sclerosis. He came to us with joints that were so stiff and muscles so hardened and cold, that he was unable to extend his legs or arms more than 5 degrees, he could not straighten his left forefinger what so ever, nor could he bend his right fingers more than 20 degrees. He therefore couldn’t even lay flat; his knees and elbows were always bent. With a combination of acupuncture, moxibustion, massage, and guided exercises throughout the week I saw great improvement. His arms were now able to straighten 95% of the way and his legs could extend by another 20 degrees. The dexterity of his right fingers had improved slightly and his left fingers began to loosen their once extremely tight flexion. His toes were now able to wiggle and flex a bit more. I saw everyday, his severe immobility turn towards mobility.

Upon assessment of his abilities and review of his CT scans and medical reports from M.D.s, we came to the conclusion that he was most likely suffering from an advanced aggressive form of Multiple Sclerosis. He came to us with joints that were so stiff and muscles so hardened and cold, that he was unable to extend his legs or arms more than 5 degrees, he could not straighten his left forefinger what so ever, nor could he bend his right fingers more than 20 degrees. He therefore couldn’t even lay flat; his knees and elbows were always bent. With a combination of acupuncture, moxibustion, massage, and guided exercises throughout the week I saw great improvement. His arms were now able to straighten 95% of the way and his legs could extend by another 20 degrees. The dexterity of his right fingers had improved slightly and his left fingers began to loosen their once extremely tight flexion. His toes were now able to wiggle and flex a bit more. I saw everyday, his severe immobility turn towards mobility.

Even though we had some great results, due to the severity of his condition, I came to the conclusion that significant lasting improvement was not within reach in a week. I also realized that palliative care to improve his quality of life would take continued daily treatment, and this man lived far away. Knowing that I couldn’t keep the family from their home for any longer, I taught his sons massage, moxibustion, and exercises in order for them to continue their father’s care at home. They said they will try and bring him for another round of treatment after the upcoming Nepali holidays. Also, while here, the family saw a Tibetan doctor, and decided to start him on Tibetan herbs long term.

Although it was difficult to let go and say goodbye, I took comfort in knowing that he would continue to be cared for by the amazing commitment and love shown by his family. -Sarah Martin

- Details

- By Kelli Jo Scott

Working with patients at the Vajra Varahi Clinic has been an interesting and amazing experience so far. We see patients just two doors down from our bedroom, so the commute is very manageable. Each morning the patients all arrive at (or before) 9am and line up outside the clinic door. If you happen to peak out the window from the second floor in the morning and they see you while they are waiting, they are quick to put their hands together in prayer and shout the local greeting of “Namaste”, which means the light within me greets the light with in you. The same thing happens if you walk thru the downstairs waiting room or see strangers on the street.

We are in the first part of our third week and I have already provided 130 treatments to patients with acupuncture, herbs, cupping, moxa, massage and just good old TLC. The patients are kind and grateful because many of them are very poor and there is no free healthcare in this region. The most common complaints we see are body pain of all types (neck, shoulder, knee, back, hand and foot), gastric pain and respiratory disorders, all of which seem to be a result of their lifestyle (just like ours are, but in a very different way.) They work incredibly hard in a physical way; in the fields, cutting grass, gardening, milking cows, cooking and carrying large buckets of water constantly. We saw some women last week carrying huge baskets of gravel (much larger than a 5 gallon bucket) on their backs with a strap going across their forehead, up flights of stairs...all in a days work! Nepalis eat very spicy foods, likely to keep food poisoning and parasites away, since there is no refrigeration here. And the vast majority of vehicles are run on diesel and DEQ has no presence here. When you are out on the roads, with the chaos of traffic like I have never seen, you must wear a mask to help keep the thick exhaust out of your lungs.

We are in the first part of our third week and I have already provided 130 treatments to patients with acupuncture, herbs, cupping, moxa, massage and just good old TLC. The patients are kind and grateful because many of them are very poor and there is no free healthcare in this region. The most common complaints we see are body pain of all types (neck, shoulder, knee, back, hand and foot), gastric pain and respiratory disorders, all of which seem to be a result of their lifestyle (just like ours are, but in a very different way.) They work incredibly hard in a physical way; in the fields, cutting grass, gardening, milking cows, cooking and carrying large buckets of water constantly. We saw some women last week carrying huge baskets of gravel (much larger than a 5 gallon bucket) on their backs with a strap going across their forehead, up flights of stairs...all in a days work! Nepalis eat very spicy foods, likely to keep food poisoning and parasites away, since there is no refrigeration here. And the vast majority of vehicles are run on diesel and DEQ has no presence here. When you are out on the roads, with the chaos of traffic like I have never seen, you must wear a mask to help keep the thick exhaust out of your lungs.

Since we may very well be the only healthcare providers that our patients have seen, it is very important that we use all of our education and skills and senses to assess each patient’s total health picture and be sure they are referred to other health practitioners if their condition is beyond our scope or if they need more emergent care. I have already referred patients for very high blood pressure, laceration and kidney infection and my colleagues have seen acute appendicitis and other cases of high blood pressure, which have also been referred. Sometimes, even then, it is a challenge to make patients see the urgency of their condition when they have little or no money.

Last week one of the patients that we were treating for post stroke symptoms passed away. We would travel twice a week by motor bike to his modest one room, dirt floor home, located in an outlying village. We would treat him there, due to the severity of his case and the transportation challenges it presented. He was very old, thin, weak and sometimes sad, but he still had his sense of humor and such a kindness about him. I am completely grateful for the experience of meeting and treating him. On the last time I treated him, three days before he died, he asked his grown son to go out to the guava tree in the yard and pick some of them. When he returned with a bag full of the ripe, luscious, fragrant fruit, he said it was for us (me and my team) who have been treating him. Guava now has a new place in my heart and I am truly glad his suffering is over. I like to think that we helped to make his last days more comfortable and less lonely. And to me, this is what it’s really all about.

I look forward to the rest of my time here in Nepal, all the people I will connect with and the wisdom that they will surely impart. --- Kelli Jo Scott

Our Mission

Acupuncture Relief Project, Inc. is a volunteer-based, 501(c)3 non-profit organization (Tax ID: 26-3335265). Our mission is to provide free medical support to those affected by poverty, conflict or disaster while offering an educationally meaningful experience to influence the professional development and personal growth of compassionate medical practitioners.