As a person that can't quite get enough of Nepal I sometimes find it hard to convey to my friends, patients and colleagues just what keeps me going back. It is a place so filled with contradiction and wonder that it just gets into your blood. Recently I read the latest book by Jeff Greenwald called Snake Lake. Jeff writes that when he first visited the Hindu kingdom in 1979 he knew that he had arrived "home". I think the Jeff and I were probably meant to be neighbors because Kathmandu also feels like home to me. Even with all its pollution, constant political upheaval and abundant poverty, Nepal never ceases to captivate my sense of brotherhood in the world.

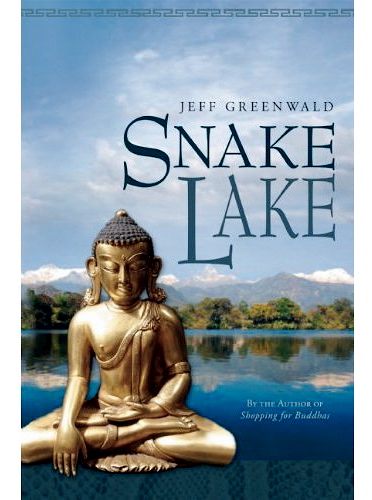

Snake Lake is an amazing first hand account of Nepal's political drama and corruption. More than that, it is a humorous memoir with a delightful introspective look at why this exotic place is so beautifully captivating. I know it is a place that always calling for me to "come home."

Snake Lake is an amazing first hand account of Nepal's political drama and corruption. More than that, it is a humorous memoir with a delightful introspective look at why this exotic place is so beautifully captivating. I know it is a place that always calling for me to "come home."

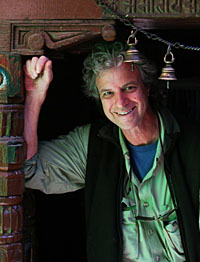

I contacted Jeff and he gave me permission to share this short article on our blog. I hope you enjoy it. - Andrew

Admin note: Thanks to Jeff Greenwald for this contribution. You can find his book Snake Lake at Amazon.com

The Facts of Kathmandu

© 2011 by Jeff Greenwald

I first arrived in Nepal as a tourist, in July of 1979. The giddy entry in my journal that day reads, “Welcome home.” Without understanding why, I’d found the place that would be my spiritual refuge and writer’s retreat for the next 30 years.

I stayed in Nepal for five months that year, and returned in 1983 on a year-long journalism fellowship. I’ve come back nearly every year since. Shopping for Buddhas, written in 1988, focused on my search for the “perfect” Buddha statue—but that theme served as a foil for exploring Nepal’s awkward entry in the modern age. My new book, Snake Lake, is set in Kathmandu in the Spring of 1990, during the often violent pro-democracy uprising. The revolution tipped the late King Birendra off his divine throne, and into a constitutional monarchy. That was when Nepal’s real struggle began.

The changes I’ve seen during the past 20 years have touched every facet of life in the country. From the Royal Massacre to the tragic civil war; from the runaway development of the Valley to the emergence of China as an eager and bossy ally. Kathmandu is no longer the place of innocence it seemed to be in the 1980s, when I shopped for Buddha statues in uncrowded chowks, or strolled down narrow lanes as sacred cows eyed me warily from doorways. When the monarchy was abolished in 2008, and a Maoist government took over, even the country’s exotic tag line—“The World’s Only Hindu Kingdom”—became obsolete.

But despite its chaos and pollution, Kathmandu is as beguiling as ever. In the late weeks of October paper kites fill the air, fragile squares jumping in the breeze. In a labyrinthine alley near the busy market of Indrachowk, necklace-weavers await customers amid curtains of shimmering glass beads. And along the funky streets of Thamel, or the alleys surrounding Patan’s beautifully restored Golden Temple, rustic shops still display a pantheon of fabulous deities: masterworks in copper, brass and silver.

Twenty years ago, combing the curio shops of Kathmandu and Patan, I knew exactly what I was looking for: a seated Buddha in “Touching the Earth” pose. The image would serve as a point of concentration, a hedge against the demons of distraction. Twenty years later, I’m not at all sure what I’m shopping for. It will have to be something reflective not only of me, but of my relationship with Nepal itself: a talisman to help me face the changes, and focus on the magic that remains.

* * *

In 1968, ecologist Garrett Hardin wrote The Tragedy of the Commons, in which he described an all-too-familiar situation in which individuals, behaving out of self-interest, destroy a shared resource.

Much as I love Kathmandu, it’s hard to visit the once charming Valley without thinking about Harding. Modern Kathmandu appears to be the product of 50 years of bad choices, one right after another. The acres of billboards, urban congestion, and maddening traffic are collective ills—but a personal trauma really brought the point home.

The day I arrived in the city I took a taxi to my flat, which I’m subletting from friends. It’s on the upper floor of a handsome brick house; prayer flags are strung across the roof. My friends had been out of town since early summer, but they told me all about the place: how they practiced yoga on the peaceful veranda, and watched sunsets from the roof. Their windows overlooked fields planted with corn, rice, and flowers.

These days, however, real estate in Kathmandu is at such a premium that open space is seen as a waste—and regulations are nearly non-existent. One month before my arrival, the fields adjoining the flat were rented out: to a glass and metal salvage business. From dawn to dark-thirty, Indian day laborers smash bottles into pieces, and hammer apart old metal gates. It's like living next to a found-art drumming troupe which specializes in abstract compositions played on bent bicycle rims, oil cans, and Carlsberg bottles.

I pack up my laptop, and escape to the city’s newest real oasis: the Garden of Dreams. Once the private estate of Field Marshall Kaiser Shumsher Rana, the Garden fell to neglect during the 1920s. After years of restoration by expert landscapers and architects (a million-dollar project funded by the Austrian Government and Nepal’s Ministry of Education), the walled compound was opened to the public in October, 2006. With its koi ponds, fountains, grass terraces, and shade trees, the Garden has become a refuge for creatures of every stripe – from songbirds and squirrels to love-struck couples and agitated journalists.

I pack up my laptop, and escape to the city’s newest real oasis: the Garden of Dreams. Once the private estate of Field Marshall Kaiser Shumsher Rana, the Garden fell to neglect during the 1920s. After years of restoration by expert landscapers and architects (a million-dollar project funded by the Austrian Government and Nepal’s Ministry of Education), the walled compound was opened to the public in October, 2006. With its koi ponds, fountains, grass terraces, and shade trees, the Garden has become a refuge for creatures of every stripe – from songbirds and squirrels to love-struck couples and agitated journalists.

In a city as manic and congested as Kathmandu, the key to enjoyment is finding hidden treasures—and the Garden is a worthy addition to the list. Here, I’m able to indulge a favorite Kathmandu pastime: closing my eyes, and just listening. The variety of sounds is amazing: a toy whistle, barking dogs, an occasional firecracker, a taxi horn, shouting voices, crows, bicycle bells, hammering on metal, children singing.

That aural tapestry is one of the things I love most about Nepal. Maybe, then, I ought to get myself a statue of Milarepa: the 12th century Tibetan poet/saint who is portrayed with his right palm cupped to his ear, listening to the music of the spheres.

* * *

Twenty years ago, phoning home from Kathmandu was an adventure. I had to figure out the time difference, then ride my bike to the Telecommunications Bureau (often in the wee hours) to place a trunk call. I’d fill out a form, take a seat, and wait two hours to learn that my mother’s line was “engaged.” If my call actually did go through, it sounded like I was talking to an astronaut marooned on Mars.

Though Nepal has entered the Information Age, an obscure law of physics still seems to forbid anything from happening efficiently.

These days, for example, making an international call from Nepal should be a cinch. One simply buys a SIM card, and dials away.

But buying a SIM card in Kathmandu first involves finding one, a scavenger hunt that makes Diogenes’ search seem straightforward. This accomplished, I’m compelled to tackle a pile of paperwork (which includes supplying, for security purposes, my father’s maiden name). I’m then required to track down a digital photo lab, where my peeved visage is captured by a gangly Nepali teen. After two hours my papers are in order. I am informed, by the phone center clerk, that my new mobile number will be active “within one day, or 24 hours, or more.”

Still, my little neighborhood—Ghairidhara—is a place where I can find just about anything: from photo labs to lime squeezers. This suits me well since, whenever I return to Nepal, I take advantage of the one thing that has NOT changed since my Buddha-shopping days: the Nepalese ability to fix anything.

In the 1980’s I was merely a spectator, snapping admiring photos of umbrella repair shops, flashlight clinics, and disposable lighter refilling stations. These days I arrive in Kathmandu with a suitcase full of items that would be discarded back home. I’m convinced that millions of dollars could be saved if the government began a space-age variation of what the British started with the Gurkhas in the 19th century. The most ingenious Nepali repairmen should be found, and recruited—not as soldiers, but as astronauts. Launched into orbit, they could repair absolutely anything--from faulty space station toilets to the Hubble Space Telescope–using needle nose pliers and a few paper clips.

In the 1980’s I was merely a spectator, snapping admiring photos of umbrella repair shops, flashlight clinics, and disposable lighter refilling stations. These days I arrive in Kathmandu with a suitcase full of items that would be discarded back home. I’m convinced that millions of dollars could be saved if the government began a space-age variation of what the British started with the Gurkhas in the 19th century. The most ingenious Nepali repairmen should be found, and recruited—not as soldiers, but as astronauts. Launched into orbit, they could repair absolutely anything--from faulty space station toilets to the Hubble Space Telescope–using needle nose pliers and a few paper clips.

* * *

The sculpture shops along Durbar Marg (across from the former Royal Palace) and in Kathmandu’s sister city of Patan (the center of the bronze-casting trade) still sell the most beautiful Buddha and bodhisattva statues in the world. Until a few years ago, the most venerated master of the art was Sidhi Raj. The elderly Patan artist died in 2008, but his students—some of whom studied with him for decades—are producing work of head-turning beauty. Their work is indisputable proof that Nepal’s ancient tradition is vibrantly alive.

I stroll down Durbar Marg, seeking I know not what. Will it be a silver Manjushri, the bodhisattva of discriminating wisdom? A lovely, lithe Tara? Ganesh, the remover of obstacles?

In the back room of the Curio Corner I find a meditating Buddha with a countenance so uplifting that the shopkeeper has to peel me off the ceiling. Equally breathtaking is a repoussé, in copper, of a flying dakini. Adorned in silver, with turquoise and gold highlights, the naked “sky dancer” is the kind of muse to keep a modern mystic up nights. I’m also arrested by a small figure of Guru Rinpoche: the Indian sage who brought Buddhism to Tibet in the 8th century AD. I’ve seen a lot of statues, but never one more superbly painted. Snow lions and clouds swirl on the sorcerer’s robes. His face conveys a view of pure transcendence, gazing unfazed into the past, present, and future. He’s clearly immune to the vagaries of change. I’m tempted, but the price (more than $2,000) is prohibitive.

Later that afternoon I ride my rented motorcycle across the Bagmati Bridge, and up the long hill to Kathmandu’s sister city, Patan. Scores of shops line the narrow roads near the old palace square, selling exquisite statuary. But what to buy? As enticing as the figures may be, none embody my hopes and fears for the fragile, beleaguered Valley.

Giving up the search, I duck through a low passage and into the courtyard of Mahabauddha: The Temple of a Thousand Buddhas. The temple’s architecture is unusual—an ornate gopala, rather than the traditional Nepalese pagoda—but what intrigues me most is a sign, nailed up on a wall across the chowk:

Giving up the search, I duck through a low passage and into the courtyard of Mahabauddha: The Temple of a Thousand Buddhas. The temple’s architecture is unusual—an ornate gopala, rather than the traditional Nepalese pagoda—but what intrigues me most is a sign, nailed up on a wall across the chowk:

YOU MAY TAKE PHOTOGRAPHS FROM

THIS BUILDING GET THE BEST VIEW OF

MAHABAUDDHA, HIMALAYAS & OTHER

TEMPLES WE ARE HAPPY TO HAVE YOU

THERE IS NO CHARGE

One pitch-dark flight of steps leads to another. Finally I reach a small brick crow’s nest, overlooking the Patan rooftops. Most of them are planted with well-groomed flower gardens, oases of color in a brick and cement city. A light breeze blows in from the south.

On the rooftop beside me, three generations of Nepalese stand together: a white-haired patriarch wearing a smart topi (the brimless cloth cap that serves Nepali protocol much like the western tie); a young man in a blue sports jacket; and a little boy. The elder holds a square paper kite in one hand, and a spool of string in the other. With the gleeful expression of a kid one-tenth his age, the man tosses the kite into the air. But the wind is sketchy, and the kite keeps dropping into the gap between the buildings.

After the elder makes several attempts, the younger man – possibly his son – takes the spool. With a few deft motions, the kite dances into an updraft and begins to gain altitude. The little boy watches, wide-eyed. With astonishing speed the string spins from the reel, and before it seems possible the kite is a speck in the sky, swooping and gyring far above the ravens and hawks. When it has all but disappeared, the boy is handed the spool. Imitating his father’s expert gestures, he steps forward to control this far-away emissary to the clouds. Though the boy has the string, all three are completely engaged. Their zeal is so contagious that I can feel the kite’s pull in my own arms.

Watching the family and their kite, I realize with a flash that this is the force the Nepalese were born to cultivate: the power of magic. The Nepalese have always shown a miraculous ability to create links, visible and invisible, between Heaven and Earth. With their incense and prayer flags, their sacred architecture and tantric rituals, their consummate skill with wood, metal and stone, the people of this Valley have spent centuries forging bonds between the mortal and ethereal realms.

* * *

In the 1970’s, there were few motor vehicles on Kathmandu’s streets. That abruptly changed in the late 1980’s, when (out of nowhere, it seemed) hundreds of Toyota taxis suddenly appeared. The plague of cars proliferated. Today, due to rising fuel costs, the latest sensation is motorcycles. There are thousands of them.

If you can drive a motorcycle in Kathmandu you can drive anything, anywhere. Granted, the bikes are small –but that’s okay, because you can’t really go faster than 30 mph anyway.

Driving is a surgical skill, accomplished with precision along narrow alleys, many of which are no wider than a cow. That’s about the width of my scooter; but I’m also sharing the lanes with vagrant dogs, taxicabs, badminton players, housewives in saris, rolling fruit, rickshaws, ice cream carts, balloon sellers, schoolgirls, buses, baskets of onions, and many other, far more aggressive, motorcyclists. There’s no room for error. If I go down, I won’t be getting up again—which explains why one friend refers to the exercise as “meditation at gunpoint.”

Riding home from Patan at sunset, I glance at the northern horizon—and nearly collide with a florist’s cart. The entire Himalayan range, from Ganesh to Gauri Shankar, towers above the foothills. The sight is so overwhelming that I have to pull over. It is impossible to concentrate on anything but the staggering beauty of those caramel-colored peaks, the smallest of which dwarfs the highest mountain in North American.

This, I realize, is why I keep coming back. I forget the bad bits, the stuff that’s subject to change. Yes, there’s a salvage yard under my living room window. True, it now takes an hour instead of 10 minutes to ride home from the Fire & Ice pizzeria. Okay, I have bacterial dysentery. These things shall pass. But the eyes of Buddha, gazing down from the Boudhnath stupa; the smell of incense in the Asan market; the frosty peak of Langtang, like a white tent looming over the Valley; those are always going to be here. What remains eternal is Nepal’s ability to thrill me, offering moment of sheer bliss between one trial and the next.

All I need to do is find one perfect statue: the single god or goddess, saint or sage, who will bring me back to such moments.

* * *

Tihar—the Festival of Lights—falls a month after Indra Jatra, during the new moon of Kartik. The five-day celebration honors Laxmi, Goddess of Wealth, who visits freshly-cleaned homes where a flame burns in her honor. Animals of spiritual significance are also fêted: every crow, dog, and cow has its day. There’s a day when sisters pay homage to their devoted brothers, and a unique observance called Mha puja: a ritual worshipping of one’s own life and body.

Tihar—the Festival of Lights—falls a month after Indra Jatra, during the new moon of Kartik. The five-day celebration honors Laxmi, Goddess of Wealth, who visits freshly-cleaned homes where a flame burns in her honor. Animals of spiritual significance are also fêted: every crow, dog, and cow has its day. There’s a day when sisters pay homage to their devoted brothers, and a unique observance called Mha puja: a ritual worshipping of one’s own life and body.

Decades ago, the only lights seen on Tihar were butter lamps: small, hand-thrown clay bowls placed artfully in windows and on rooftops, each with a woven cotton wick. This year, as I wander through the crowds filling Asan and Indrachowk, the vast majority of lights are electrical. Garish Christmas-style decorations blink and flash, the banks and corporate buildings garlanded with especially ostentatious displays. It’s a vision from Disneyland, or Las Vegas: eye-catching, but somehow soulless.

Suddenly, there’s a deafening BANG: an overloaded transformer shorts out, showering the street with sparks. Indrachowk is plunged into darkness. Or near darkness; hundreds of little clay lamps, previously obscured, flicker into view. They glow from windowsills, rooftop planters, and the wooden workbenches in cobblers’ and electricians’ shops. A reverent hush descends on the crowd. Children reach for their parents’ hands. Everyone seems transfixed, the fortuitous black-out evoking memories of an almost mythical time, not so long ago, when Kathmandu Valley was still a place of enchantment and mystery.

A minute later, the lights blink back on: power is restored. And at that moment, I hear something extraordinary. A collective groan of disappointment rises from the streets—as if a magic carpet has been snatched away from beneath us.

At that instant, I know what I will bring back from Nepal. It will not be another Buddha, Ganesh, or Tara; it won’t be Milarepa, or Manjushri. Only one object—fragile, but timeless—can affirm my attachment to Kathmandu, and remind me of what I always come here to find.

Near the thronged intersection of Indrachowk and Asan I find a small ceramics shop, tucked between a cyber café and photo shop. I purchase a dozen little clay bowls – and a package of woven wicks.

* * *