It’s difficult not to look at the mountains. Those majestic, jagged peaks piercing the clear blue horizon tug at my peripheral vision. “Focus!” I say in my head as our group of four small motorbikes meander along the narrow road. The edge drops away and it's not hard to imagine what would happen if you were to drive off. In Nepal, these are considered “the hills” but they would certainly be called mountains in most other countries. The steep hillsides are covered in terraced fields, many of which are chartreuse with the winter crop of mustard in bloom. It is a frosty December morning and my fingers are tingling with the cold as we make our way to our new outreach clinic in Mahankal.

It takes about an hour for our impromptu motorcade to reach the village of Mahankal, a small Tamang village at the very extent of our catchment area. In addition to the two large backpacks containing our clinic supplies, we arrive with three acupuncture physicians (two Nepali and one American), two Tamang-speaking interpreters, a videographer and myself. We are here to assess the health of this village by providing some basic screening as-well-as offering medical advice and lifestyle education. It is a remote village and many of our new patients have never seen a doctor before. It is easy to understand why as it is a strenuous two hour walk to the nearest government health post and an expensive several hour ambulance ride to the nearest hospital.

The Tamang ethnic group originally settled in Nepal several centuries ago from Mongolia. They are an imposing, stout, mountain people, surviving as subsistence farmers. They maintain their own language and observe their own holidays and traditions. Many of the older women display facial tattoos and piercings adorned by gold jewelry. They are superstitious, known for their hard work and can be very skeptical of outsiders. That said, we have managed to forge some inroads with this community over the years by providing other outreach clinics in the area. Many of these villagers already know us and have visited our clinics in the past though we have not operated in this area since the beginning of the pandemic. As we arrive we are greeted with smiles.

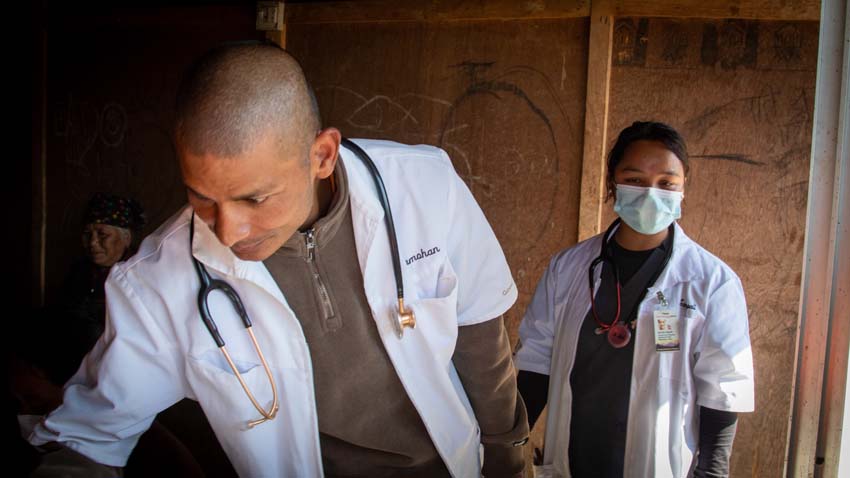

On a previous visit to this village we were offered the use of a couple rudimentary rooms in a dilapidated community building. This is where we will work, two days a week, for the next several months. Today, a handful of local men help us by producing a couple wooden tables and a dozen plastic chairs. I watch with pride as the team, led by Satyamohan, quickly moves into action cleaning the floors and preparing to receive patients. In the past it has been our foreign practitioners leading these efforts but now our Nepali staff shows us what they are capable of.

Since 2020 (the dark days of the pandemic) our project has become fully staffed and sustained by Nepali manpower. Practitioners, interpreters and support staff which we have trained and mentored for many years have now taken the lead in our operations. They manage all of our clinic operations including the hosting and supervising of our foreign volunteers. This is my first opportunity to observe them setting up a new outreach clinic and I am more than impressed.

Our model is simple. Through our experience working in Nepal, we know that most of our patients are coming to us because they suffer from chronic pain. Their bodies take the toll for a lifetime of farming and carrying extremely heavy loads up and down these “hills”. For this, acupuncture is an inexpensive and effective medicine. The magic of acupuncture lies in frequent, repeated treatment over several weeks. This time offers us the opportunity to form better relationships with our patients. We are able to take a more exhaustive health history over several visits and screen for many diseases that the patients themselves may be unaware of, such as diabetes, heart disease and upper respiratory diseases. These are referred to as non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and our goal is to prevent and/or detect these diseases early. This requires broad health screening and a lot of community education.

Before long there is a small crowd of people gathering around our reception table. Sanita Gopali has set herself up to administer a battery of health assessments including vital signs, blood glucose and a basic health history. Even as a native speaker in Nepali she sometimes struggles to make sense of the local dialect and has to refer to one of our interpreters.

Sanita is in her mid-twenties and grew up in a small village near our primary clinic in Bajrabarahi. She initially joined one of our interpreter trainings that we conduct during the summer. This six-week course is an opportunity for local young people to improve their English speaking abilities by working with native speaking foreign doctors. It also exposes them to the concept of community centric health care and the use of acupuncture in the management of chronic pain. After the training, Sanita was invited to join our team as an interpreter. She proved to be an exemplary student and soon became a reliable clinical assistant to many of our volunteers. Seeing first hand the effectiveness of our clinic, Sanita became very interested in learning the medicine for herself. She applied for and received a government scholarship to attend a small, three-year, acupuncture school in Kathmandu. Upon graduation she rejoined our team as a clinical intern in 2022. Today, I marvel at how she has transformed into a confident and knowledgeable practitioner. Very comfortable wearing her white jacket and interacting with the throng of people surrounding her. Within the first 30 minutes, Sanita catches a patient with an undiagnosed heart arrhythmia. While she writes up a referral letter for the patient to receive an ECG, she councils the patient about the urgency of seeking this care. She also red flags the chart so that we will be sure to follow up on this case.

While Sanita is doing her magic, I watch as my friend and clinic manager Satyamohan Dangol directs the team and prepares for his day. Satya and I have been working together since we began the project in 2008. The shy and soft spoken eighteen-year-old was my first interpreter and as we got to know and trust one another, we quickly developed into an effective team. Satya is now a skilled and fully licensed medical provider. Today he confidently leads his team with practiced expertise. In his tiny, poorly lit treatment room sit seven or eight patients with a few more peering in through the open window. Satya also struggles with the Tamang dialect from time to time but he patiently looks through their medical reports, X-rays and medications. For most of them, this is their first encounter with a doctor and they listen attentively as he speaks.

Periodically he calls me in to consult about a patient. First we look at a petite elderly woman who is clearly in a lot of pain. Her sternum protrudes unnaturally and is visible through her clothing. She tells us that it appeared after she took a fall about a week ago. We perform an examination and conclude that she likely has a compression fracture in her upper thoracic spine. Likely secondary to advanced osteoporosis. Satya writes a referral letter and gives it to her husband, explaining to them that they need to take our letter to the government hospital in Kathmandu. He then performs some simple acupuncture to help the women with her pain before sending them off. Next, we are examining a one month old infant who is having some breathing difficulties. Satya and I both listen to the baby's lungs and assess his vital signs. We are concerned by his irregular breathing, high respiration rate and the significant wheezes we hear in his lungs. Satya calmly explains our concerns to the mother who agrees to take the baby immediately to the government health post for further assessment. Satya provides the woman with a written report of his findings which includes instructions for the receiving health workers. Satya then hands me a set of MRI films and a stack of medical reports which are all enclosed in a plastic bag. “This patient is coming in this afternoon. Can you have a look while I treat some of these patients?” I take the reports and he disappears into his treatment room.

I spend the next hour trying to understand the myriad of hand written reports. A thirty-two year old woman started having unexplained weakness in her right arm about a year ago. A post surgical report from eiight months ago suggests that she received a decompression of the upper cervical spine… hmmm… for what? Did it work? Did she receive any kind of rehabilitation? It’s unclear. I can see on the MRI films that the patient has a Chiari malformation. This is an uncommon birth defect in which the brain stem extends down onto the cervical spine. Generally these don’t cause too much of a problem and most people who have them are unaware of the condition. This one however seems to have caused a spinal syrinx (a fluid bubble in the spinal canal). That is a problem. It appears that this is most likely what the surgery was intended to reduce. I give my report to Satya and we discuss the assessment that is necessary. Later in the day the woman comes into the clinic and as expected she is partially paralyzed in her right arm and hand. Satya performs several neurological tests and then outlines a treatment plan to the women. He explains that he has a lot of experience working with paralysis and that he is reasonably confident that he will be able to recover some of the function of the hand. He set some base-line measures and they agreed to work together for the next several months.

Forty-eight patients later as the sun sets below the rim of our valley, the temperature turns chilly. The motorbikes carrying our team arrive back in Bajrabarahi. Hungry and tired, our crew pull off their helmets while they chat excitedly about today’s new clinic adventure.

For me it is like seeing the project for the first time. This team of Nepalis, made up of young adults, somehow adopted this idea of how to improve the health of their communities and have now made it their own. They might lack the expensive formal education that many of our foreign volunteers bring to the equation but they do not lack experience, innovation or fortitude. Today, I witnessed a professional and dedicated team provide necessary services to an unseen and underserved community. It is no small accomplishment and I am sincerely humbled by their beautiful work. --- Andrew

Author: Andrew Schlabach, AEMP LAc

Director, Acupuncture Relief Project

Bajrabarahi, Thaha, Makwanpur Nepal

I want to thank the many volunteers and donors that make this work possible. This project in Nepal has exceeded my wildest expectations and has touched the lives of (literally) thousands. My family of friends and colleagues in Nepal and around the world have forged something that I think is truly unique. We continue to develop our vision of an inexpensive and effective health model which works in conjunction with Nepal’s existing system. We strive to provide personalized, compassionate care to not only help our individual patients but also to improve the communities overall wellbeing. Ultimately resulting in a reduction of preventable diseases.

Lastly thanks to the generosity of our community of support, I was able to make good on my promise to provide our Didis (dee dees) with a washing machine. Sakali and Dipmaya hold our team together by cooking our meals, cleaning the facility and washing all of the clinic’s laundry. After seeing the joy on their faces I have to admit that I was a bit ashamed that it took me this long to address their needs. Thank you Didis for all that you do to make our project successful.