Acupuncturists As Transformative Providers In Rural Healthcare

When Andrew Schlabach and I co-taught a five-day seminar in Kathmandu this November, our purpose went far beyond skills training. Yes, we covered practical techniques in structural diagnosis, primary health assessment, and scalp acupuncture, but at its heart, this seminar aimed at something much larger: bridging medical paradigms to work toward a new vision for healthcare in rural areas.

Acupuncture is unique in that it sits at the crossroads of modern and ancient medical approaches. It’s a form of medicine with extensive modern research to support its efficacy, yet it originates from a holistic paradigm that views the human body as a microcosmic reflection of the larger planetary system. While acupuncture is not traditionally part of Nepali medicine, it offers the ability to address modern challenges like pain management and NCD screening while honoring the spiritual connections and more eco-friendly tools inherent in many Indigenous healing traditions.

In Nepal, acupuncturists working or volunteering with ARP/GHN often serve as the first point of contact in rural areas where healthcare options are limited. Patients frequently seek us out for pain relief, but these interactions create an opportunity: while addressing complaints like pain, insomnia, or moderate mental health concerns, acupuncturists can also screen for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, hypertension, or chronic respiratory illnesses. These conditions often take years to manifest clinically and earlier diagnosis is related with better outcomes for patients.

A recent case illustrates this potential. Last month, one of our volunteers, Jenn McCoy, noticed a patient with a pain condition who also had a cough. When Jenn measured her vitals, she saw that the patient’s oxygen saturation was low, and her respiratory rate was high. This prompted Jenn to listen to the patient’s lungs, where she heard consolidation. Jenn referred the patient to the health post for a chest x-ray to rule out pneumonia, which was confirmed. The patient was prescribed antibiotics, and within a few days, her cough improved significantly. This example highlights how acupuncturists, equipped with the right tools and training, can play a crucial role in identifying and addressing conditions beyond their primary focus.

The philosophy of acupuncture has always emphasized early detection and the prevention of imbalance, making it an ideal modality for integrating NCD screening into rural primary care. This alignment of principles allows acupuncturists to be a cornerstone in addressing Nepal’s growing burden of chronic diseases.

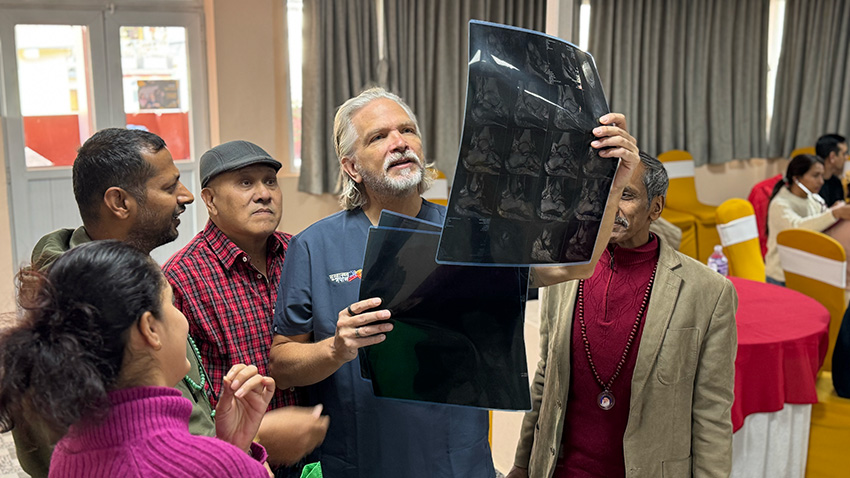

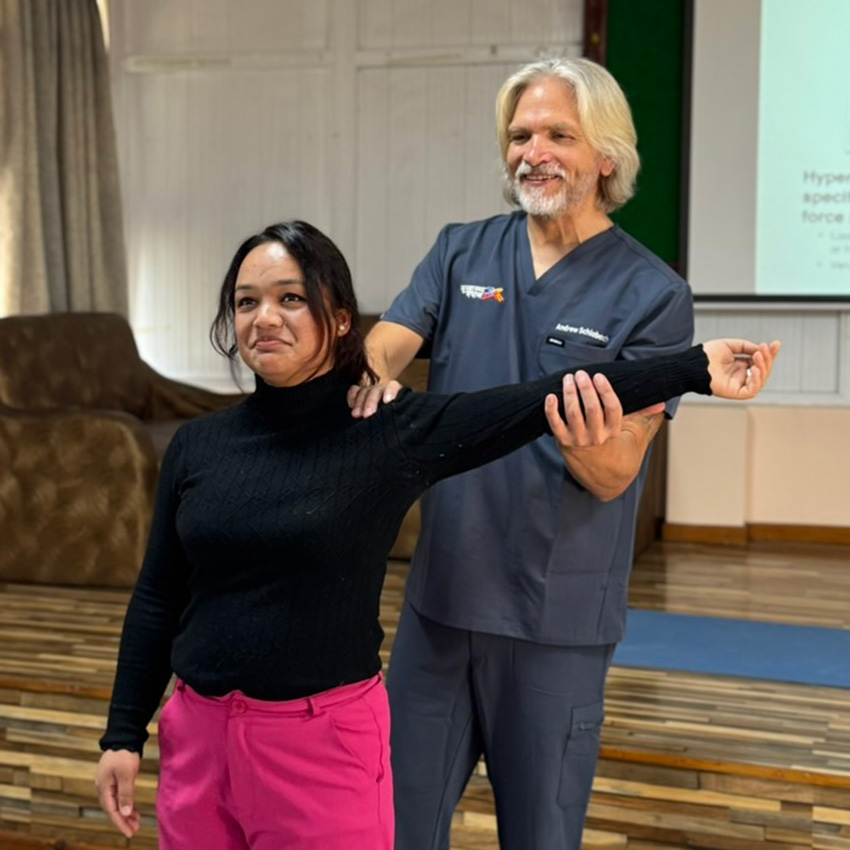

At our Kathmandu seminar last month, Andrew provided each participant with a vital signs kit that included essential tools like a blood pressure cuff, stethoscope, thermometer, and pulse oximeter. Alongside these tools, he introduced laminated reference cards designed to make critical information easily accessible during clinical work. One card focused on NCD screening, detailing blood pressure thresholds, normal oxygen saturation levels, and other vital parameters to help identify early warning signs of conditions like hypertension or diabetes. The second card highlighted structural diagnosis techniques, offering guidance on musculoskeletal assessments, normal range-of-motion values, and key orthopedic tests. These cards served as both practical tools and symbols of our larger vision: empowering acupuncturists to combine modern diagnostic skills with their holistic practice. By putting this information directly into their hands, we aimed to bridge the gap between theory and application, equipping them to provide patient-centered care that is both evidence-informed and attuned to their patients’ needs.

The impact of the seminar is already taking shape. One student has organized an NCD screening camp with other members of the class to begin practicing their skills in rural areas. He’s even creating a checklist to guide their assessments based on what they learned during the seminar. It’s inspiring to see how quickly they’ve taken initiative to apply their knowledge, creating opportunities to improve health outcomes in their own communities.

For those interested in how we envision integrating these ideas into larger healthcare systems, we’ve written more about this concept in our article: Proposed Healthy Lifestyle Center Model Utilizing Integrated Primary Care for Non-Communicable Diseases Prevention and Management in Rural Nepal. ARP/GHN in Nepal serves as a model for how acupuncturists can lead in this transformative approach.

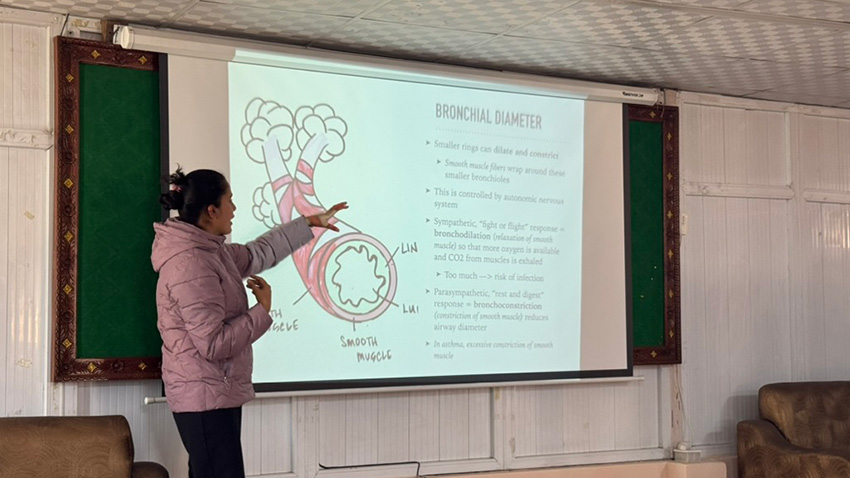

My contributions to the seminar focused on pathology. I taught the mechanisms of diseases like arteriosclerosis, congestive heart failure, asthma, and COPD. These conditions are on the rise globally and in Nepal. Understanding these diseases’ progression, warning signs, and impacts equips acupuncturists to act as both caregivers and early detectors.

In the afternoons, I taught scalp acupuncture, a modality for treating neurological and pain-related conditions. Watching the students practice on each other was inspiring, as they recognized how these techniques could profoundly benefit patients with post-stroke paralysis, emotional imbalances, or chronic pain.

These lessons were about more than just technical skills. They were about showing how acupuncture bridges seemingly disparate worlds: the biomedical emphasis on diagnostics and measurable outcomes, and the holistic traditions of balance, connection, and prevention.

In many rural areas, patients often seek Shamans or local healers for their care. Acupuncture, with its holistic roots that focus on cyclical correlations feels approachable and trustworthy to many patients. It also acts as a bridge to modern healthcare systems, helping patients navigate complicated medical pathways in ways they can understand and trust.

This dual role allows acupuncturists to serve as mediators, connecting patients to both traditional practices and modern medicine. For example, a rural acupuncturist might use pulse diagnosis to assess imbalances while taking blood pressure to screen for hypertension. They might treat pain with acupuncture while identifying red-flag symptoms that require referral to a hospital. This versatility makes acupuncture a vital link in Nepal’s evolving healthcare system.

Nepal faces serious healthcare challenges. NCDs, often called “silent killers,” take years to develop but are among the leading causes of death worldwide. Early detection is critical, yet rural Nepalis often lack access to regular screenings or preventive care.

Acupuncture offers a solution, not just as a treatment but as a way to bridge healthcare gaps. Its research-based efficacy ensures it fits into modern systems, while its holistic roots resonate with traditional values. This duality makes it uniquely positioned to transform rural healthcare in Nepal and beyond.

During and after the seminar, I was inspired by the students’ enthusiasm, their willingness to learn and apply new skills, and their dedication to their communities.

If we continue to support acupuncturists as rural healthcare leaders, equipping them with the tools, training, and confidence to bridge medical systems, we can create a more integrated, effective healthcare system in Nepal and actually, in the US too. A system where traditional medicines and innovation coexist. A system that prioritizes prevention, accessibility, and patient-centered care. A system where every patient receives the care they deserve.

This is the future I believe in and one I’m honored to help build. --Dr. Bex Groebner