“Finding our own definition of success means becoming aware of what we value. Often, this means rinsing years of conditioned thinking from our minds.” - Anonymous

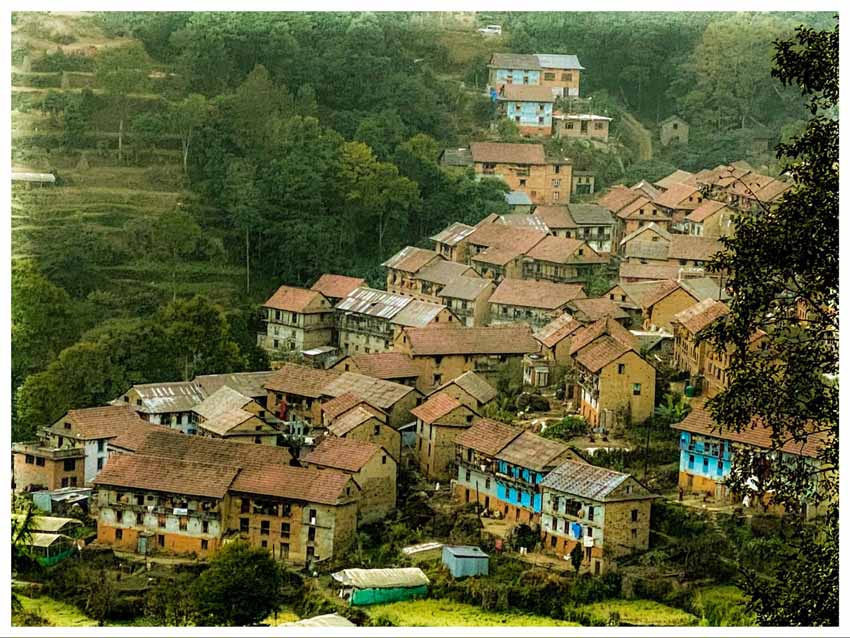

I recently returned home to Portland Oregon after spending two months working as a volunteer at Acupuncture Relief Project (ARP) in rural Nepal. Within my first year of school at Oregon College of Oriental Medicine I knew that after I graduated from my MAOM program, I wanted to go work for ARP and Good Health Nepal. At that time, little did I know what it would actually mean for me professionally and personally. I can say without a doubt, working in an integrated clinic in rural Nepal these last few months was the most transformative journey I have ever undergone. To emphasize the enormity of such a statement I would like to share that my background includes extensive travel to 27 countries, 7-years as an Expat in Spain, two Master’s programs, 4 businesses (2 sole proprietorships, 2 LLC’s), a professional career in Business Admin, a significant history of personal health challenges and a recent separation from a six-year marriage.

Not many TCM students get the opportunity to be thrown into a clinical setting as intensive as I experienced in Nepal, especially right after graduating. It was my first post-grad discovery on what it really meant to be someone’s primary care provider and case manager. In seven weeks I saw 480 patients, averaging almost 14 patients per day on a six-day work week in very rustic conditions. During my time there I treated acute and chronic pain of every single musculoskeletal problem imaginable. I had to monitor COPD conditions and evaluate EENT problems. I took on 4 patients dealing with stroke sequelae rehabilitation, screened for autoimmune diseases, treated wounds, infections, hernias and urogenital issues. I had to deal with super scary unmanaged diabetes and hypertension cases. And I saw significant evidence of substance abuse, and mental and emotional trauma.

Many of the patients under my care had never before seen a medical provider. I was their initiation and first experience. At ARP, volunteer acupuncturists are required to perform as primary care practitioners. We had to assess lab work, understand medications, read health records, screen patients for hypertension, diabetes, infections, establish treatment and manage continuing care plans. I sent patients for thyroid testing, urine and stool testing, CBC’s, RA Factor, and multitudes of gastrointestinal testing. Access to a lab strengthened my ability to give exemplary primary care by providing objective evaluations, diagnosis and appropriate referrals. While the majority of our profession in the States are not required to act as primary care providers, nor make the kinds of decisions I had to make at ARP in Nepal, it taught me an invaluable lesson of practice based-learning and improvement and how to enact a systems-based approach in that limited environment. Before going to Nepal, my mindset was very much in the Eastern medicine camp. Although my clinical training included experiences at Good Samaritan Hospital and Providence Oncology Center in Portland, I had not yet truly understood the value of an integrated system. Nor had I realized my full potential and role in an integrated system with the responsibility of providing patient centered care, and the acknowledgement and practice of doing what is best and correct for the patient, that may or may not include acupuncture or Chinese medicine. During my time there I learned the value of sending patients to get lab work done, what acupuncture will never be able to help with and what my limitation as a health care provider is really all about.

Two days after arriving at ARP's main clinic I accompanied Andrew Schlabach, APR's founder and Project director, on a home visit to see a patient that had just suffered a major hemorrhagic stroke a few weeks prior. To understand the challenges the people of Nepal face trying to get to healthcare can not be over emphasized. Our journey to meet this man began with a 30 minute motorcycle trip "up the hill". A winding, dusty, rocky road straight up the mountain, dodging stray dogs, goats, cows, country traffic of pedestrians, other motorcycles, tuk tuks, passenger lorries, and the occasional car. All this while carrying the entire equipment necessary to evaluate this man.

Upon arrival, I met a barely coherent 62 year old male in a wheelchair, perched on the porch of a four room concrete house that was only accessible 150 yards down a single track goat trail from the main road. The stroke had left the entire right side of his body paralyzed, inability to speak, understand his surroundings, or walk. He was at the mercy of his family, friends and neighbors, who all stood around curiously as I began to evaluate his vital signs. Needless to say, this was a jump in with both feet type of moment. I had never treated such a sick patient in such austere conditions in my life, and that was only week one of my seven weeks of volunteer work in Nepal.

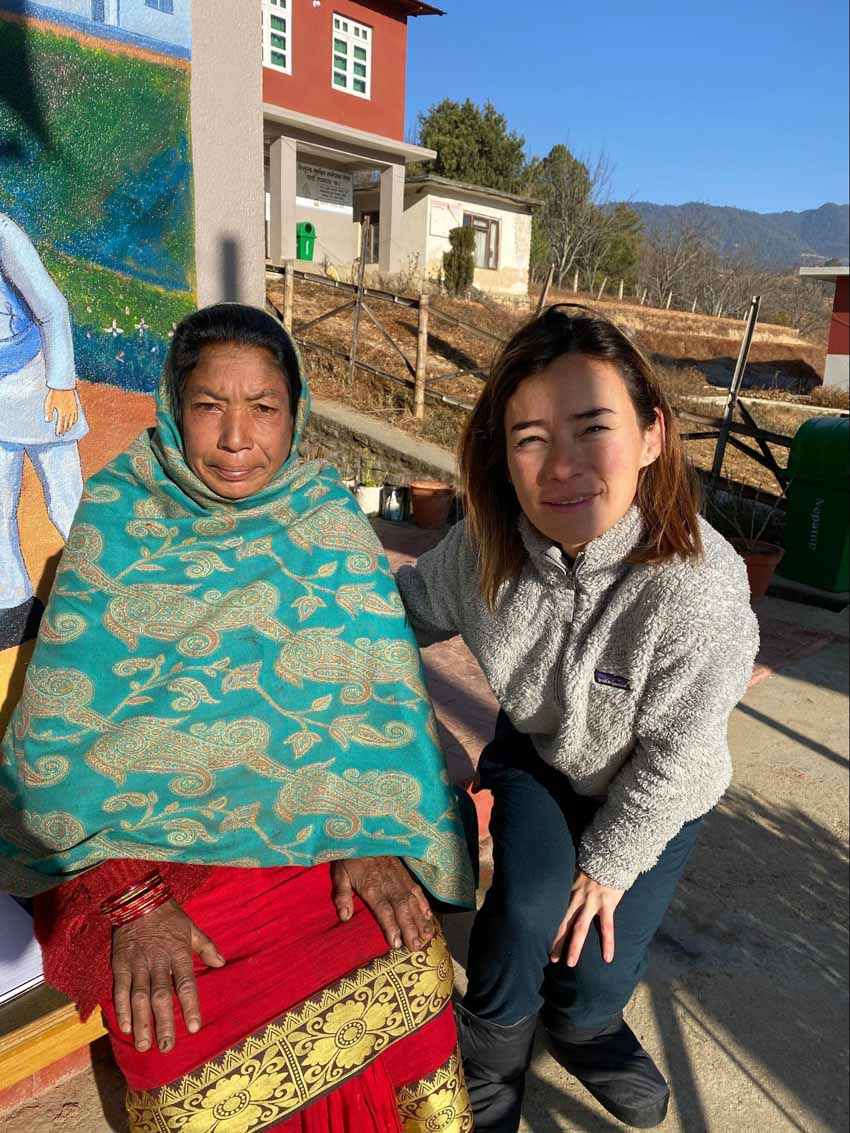

In my third week I had a 71 year old female come to the clinic, a trip that took her nearly five hours with the assistance of her son and daughter-in-law. Her chief complaint was excruciating left knee pain, which was about the size of a small melon. After reviewing her x-rays and doing a knee exam, it was very clear to me, even with no background in radiology, that this woman's knee was totally overcome with osteoarthritis, almost non-existent cartilage, and ligaments like noodles. The only thing that would help her walk again would be knee replacement surgery. In most developed nations this is doable. For people scratching out a living in rural Nepal, this is a very limited to near impossible option. She looked at me point blank and asked in Nepali without even looking at my interpreter and said "Can acupuncture fix this? Can you get me to walk again?" and with a huge lump in my throat I replied, "No. Acupuncture can't help this." It was an extremely humbling moment considering how much effort she had gone through to get to the clinic. This pushed me to extend myself and explored what options were available and what I could actually do to help this patient.

Week five started out finding one of my stroke patients in severe distress with declining vitals. Red flags are something we are trained to look out for, but as a new practitioner I had yet to catch, assess and act on a red flag. My patient clearly needed to get to a hospital but we were in rural Nepal and the hospital is 3 hours away in the capital. With ARP's assistance I had to jump into action and make that happen. I never saw that patient again as he had to remain in hospital for several weeks thereafter. That moment was a turning point for me that really solidified the importance of grassroots organizations like ARP and the healthcare challenges so many people encounter all over the world in rural areas with extremely limited resources. I was reminded once again how fragile life can be and it emphasized what little time we really all have.

During that same week I had come across an article posted in The New York Times that highlighted research showing how the most difficult time of any project, adventure or goal was the midway point. The term "half-way there" was coined a motivational Death Valley sinkhole that threatens successful outcomes and derails best intentions. At our end-of-week recap meeting, Andrew ended on the advice to keep leaning in and stay present rather than dwell on end of camp holidays or exiting plans. Even though I admittedly had spent a few hours that week researching and booking travel plans for my return to Kathmandu, I honestly felt it had been a week of major revelations for me in my professional development and personal recovery. The term 'halfway there' had been more about deepening relationships with my patients, getting to know their personalities, witnessing their developing trust in me as their healthcare provider and finally finding self-confidence about utilizing and optimizing all the training I had received thus far. Now as I reach the proverbial halfway point of my own life I am questioning so much of what is emphasized in the West as the important things in life. For me, love, freedom, health, purpose and community have become the compass by which to steer, and all else will always derail best intentions.

The weeks flew by and all that I saw and all that I did left their marks on me. Exhausted but grateful that I had arrived at the end of camp with my health mostly intact, a brain full of all new concepts and a stable foundation for my own healing. I’ve always believed that chance favors a connected mind, and for a shift in perspective to truly make a significant difference in one's life it usually occurs organically and unexpectedly. The seven weeks of volunteering at ARP opened me up and challenged my perspectives. It fine tuned my values, cleared out stale ideas and stuck emotions.

After leaving ARP I ventured on to Pokhara, a beautiful mountain hippie trekkers town about eight hours west of Kathmandu. I sat at breakfast one morning chatting up a new friend from Austria who had only just arrived the day before. She had been volunteering in India and was just about to return to Goa for a month internship as a psychotherapist. We swapped stories of volunteering and what we had encountered during our time there. Both of us seasoned travelers, but first time volunteers, we debated current world governments, social structures, resources and the glories and hardships of the human being. All this went down over fluffy eggs and pancakes with bottomless lattes. I won’t even minimize how much I missed the comforts of western food after 7 weeks in rural Nepal. Dal Bhat, a traditional lentil soup found throughout Nepal, India & Bangladesh, had become a running joke among my fellow western ARP volunteers and even the occasional stranger. A Japanese man who I briefly shared a taxi with proclaimed that he loved his trekking adventures in Nepal but was ecstatic to be leaving Dal Bhat behind!

The thing I love most about traveling is the surreal time warp you experience in leaving the bubble of your comforts, your expectations, and if you’re lucky, your prejudices. So that you can briefly become aware or be reminded that life is happening, now, at every moment, for all kinds of people (and animals!) with every possible capacity all over the world. In places and manners that may be nostalgic, or may surprise and shock you. And then, it all comes snapping back like a slingshot, the “reality” of your life, your history, your home, as you arrive safely back. Traveling allows us to change aspects of ourselves temporarily. We know that at some point we get to return to the familiar and there’s a security in that. It’s even true for Dal Bhat! As one Nepali colleague from ARP affirmed, how much she missed her home food after spending three weeks in China during our camp.

My new Austrian friend and I discussed these ideas at length and we both agreed on two key things. First, that all people everywhere regardless of background just want to feel healthy and secure with basic needs met, at the very least. And secondly, while we from developed nations may believe people from developing nations are missing out, it may not be entirely true. What we have in material wealth we often lack in feeling of connection or purpose. Namaste is a word that is used to say hello and goodbye in that part of the world. Back home, it’s something you might mutter awkwardly at the end of your yoga class. But ‘namaste’ is really about making a connection, it means ‘I see the divine in you’. So for two months, every time I spoke to another person, I started with “I see the divine in you...”. What a powerful way to begin and end an interaction! This really hit home for me towards the end of my time at Acupuncture Relief Project and Good Health Nepal. Emotions ran high during the last week of camp as I wrote my continuing care letters for the next practitioner who would take my place. Many of my patients were very concerned I was leaving, after all we have really just gotten started! And many asked when, not if, I would be returning and told me I had made a huge impact in their lives. Several patients always greeted me with the more formal version ’namaskar’ which is reserved for elders or persons of high standing. To be honest, I felt honored but a fraud. Did I deserve to be greeted so highly? Who am I? I was just a new graduate fresh out of TCM school, and had felt completely inadequate for most of the conditions I had to treat. But I realize now that practicing medicine is not just about tests or pharmaceuticals or disease. Most often it’s about being listened to and heard, about being seen and respected, and finally about feeling connected and taken care of.

Collaborative patient care between Eastern medicine and Allopathic medicine is in its infancy here in the US. And as our profession gains traction in communities, hospitals and government public policy, we have an opportunity to influence that merging of medical worlds. Achieving this requires training and education from TCM schools and internship programs like Acupuncture Relief Project, that give us the knowledge and authority to participate in screening, medication-based collaborative care and confident patient case management and referrals. Acupuncturists typically are last resort practitioners that patients go see after they have seen everyone else. Chinese medicine is as much about prevention as it is correction. And practitioners in our field have much to offer by the very way our medicine and our training centers around holism and connectedness. My vision of an integrative system means eliminating these ideas of last resort and making Chinese medicine and acupuncture a key part of someone's initial primary care, as is done in most parts of Asia.

My time in Nepal made me feel incredibly grateful. What does the word gratitude really mean or more importantly, how does that feel? As a volunteer it’s something you really do get to experience, both within yourself and from others. As I boarded my plane to return to Portland Oregon on my last day in Nepal, it felt like a huge tingling lump in my throat, with my heart full but elated, my eyes moist with sadness, but a small smile on my face. I left knowing I did my best, and perhaps I made an impact, however small or short. I went with clear intentions and goodwill and had constantly been shown so much goodwill in return. I am back State side and as I decompress and reflect on my time there I realize I am forever permanently changed and for that I am truly grateful. For the experience, for the friendships formed, ARP’s support and faith in me as a practitioner and the community it has created, but most of all for the Nepali people. Namaste! ---Tameka Lim-Velasco