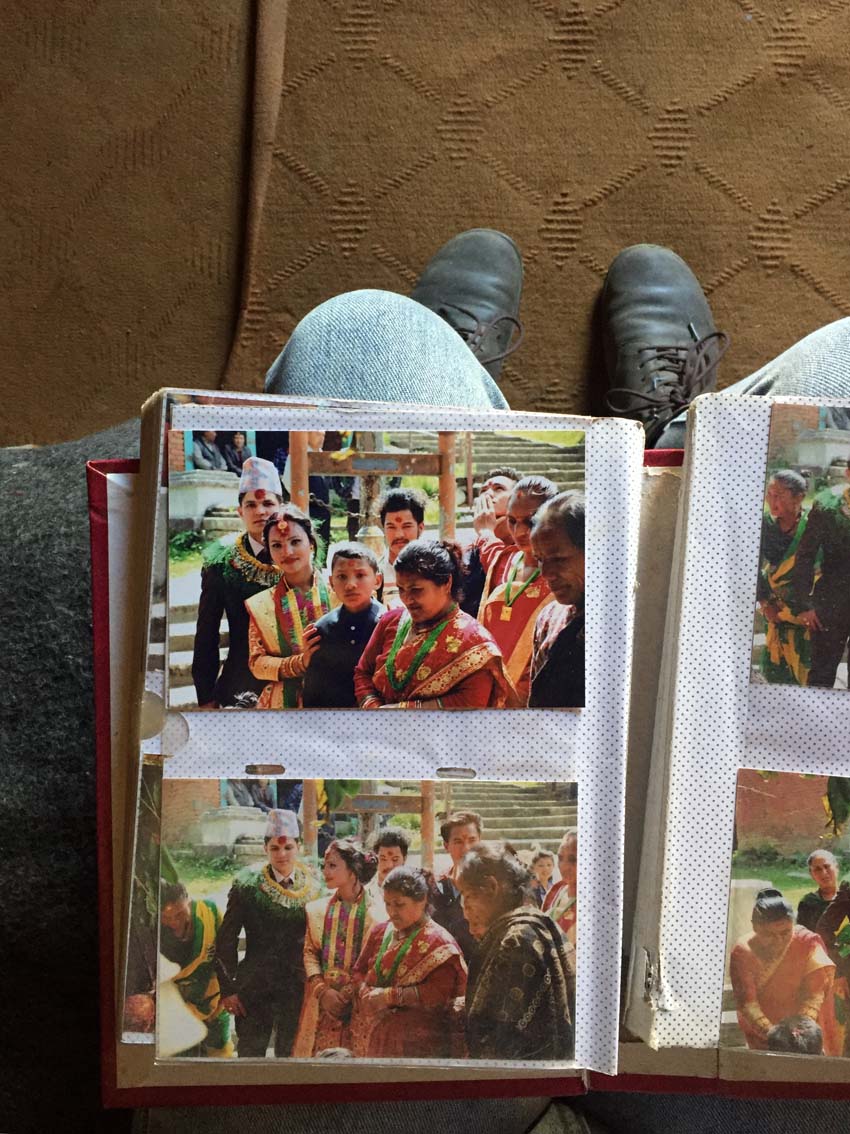

Cricket highlights are buzzing in my left ear, as I peel apart crinkling, plastic sleeves of a wedding album. My patient’s fourteen-year-old son splits his attention between the static screen and his sister’s wedding photos, dutifully providing me with descriptions of each face’s relation to the family.

“Mother’s big sister’s husband.”

“New husband’s mother’s big mother.”

Overhead, two occupied bird’s nests are harmoniously integrated into the wooden beams and cool clay of this traditional Newari home. An ornately carved shutter is open, shedding warm sunlight on my lap to compliment the sticky-sweet, masala tea in my hand. I am beginning to feel more healed than healer, the boundaries dissolving between myself, the soft, fleece couch cover beneath me, and the mother and son flanking my sides.

My patient’s charm is contagious. A muscular woman in pink who doesn’t rise past my breast, she pulled me in from the street, scythe in hand. She is beaming at her doctor’s compliments of her daughter’s beauty, which are completely sincere. The twenty-two year old bride’s smile outcompetes a heavy red tika, layers of bright cloth, and grass, glass, and metallic adornments. Her son tells me she lives in Baltimore, and I am excited to convey that I share a coast with his sister, as we three sit atop each other on the small couch.

I hear heavy footsteps below, and quite suddenly the television’s light is extinguished and the photo album stowed away. I greet my patient’s husband, “Namaste”, and receive a stoic acknowledgement. My patient is bringing her fingers to her mouth, offering me to join their morning meal. Feeling as though a storm has moved in, I enthusiastically thank them and take my leave. My thoughts wander to the metronome of my footsteps… is my patient seeking relief for more than her inflamed elbow?

In the clinic, Nepali women’s hot, swollen, cobbled knees and spines contrast my cold, pale fingertips. From pubescence, they have carried 100 pound loads on narrow, arguably vertical dirt paths. Many married and bore children before twenty, adding to the weight of their responsibilities. Their jaws drop when they learn that I, a waifish twenty-eight-year-old, am not yet married. “No boyfriend?”, my interpreter relays, blushing. By my age, their bones are rubbing against one another as they prepare for (or enter) grandmotherhood.

Most Nepali women I encounter in clinic seem to flourish within this structure. When asked, they proudly count their sons and daughters on their fingers. Seated beside each other, they enunciate as though on stage, stretching some syllables like taffy and hitting others like a snare drum. A couple arrives as though on a date. Like satellite dishes, their ears orient to eavesdrop on the other’s appointment, assuring the best care for their other half. Next door, our young female interpreters giggle in the office as they discuss their prospects, excited to carry forth the traditions of their mothers and grandmothers.

There are no discussions of “co-dependence”. There are no illusions that one half should stand without the other, though they often are at work apart. Marriages are the building blocks of their families and communities, and a strong foundation is made of stable partnerships. They do not reenact the dramatic, tumultuous romances of The Notebook, Titanic, and Twilight. Couples do not embrace in public. Like the sun and moon, husband and wife understand the virtues of rhythm, dependence, and distance.

After clinic, I walk to the bazaar to get honey. I can choose “big or little” Dabur honey from one of a couple stores. Unlike in an American grocery store, I am not overwhelmed by choices like organic or inorganic? Clover or wildflower? Squeeze-bottle or jar? Raw or pasteurized? Local or imported? I do not spend ten minutes staring at the discounted jar of muddy, “Chai-flavored” honey, wondering if it will spoil my morning cup of tea. Walking back to the clinic, I never question whether I bought the wrong honey at the bazaar, because I bought Dabur: the only honey at the bazaar.

I imagine most women feel similarly at ease in their familial structure. Expectations of them are clear and, for most, achievable. They work hard in a lush landscape, like their mothers and daughters, and are rewarded with family, community, and a harvest. Most of their decisions are deferred to their male guardian, whether a father or husband. For many women, the Nepali family unit works… until it doesn’t. When a woman’s guardian acts outside of her best interest and safety, the limited choices of Nepali women become dangerous.

An elegant Nepali woman in her early twenties lies on my treatment table, stiffly and gingerly indicating at her nape. The pain is untouchable, both in its vague, migratory location and her reactivity to my hands search for it. Feeling the tense, floating quality of her pulse, I draw the curtains.

“How is your home life?”

Her eyes gloss over and overflow, tears soaking the fine, dark hair at her temples. She tells a familiar story: alienated in her husband’s home, overwhelmed by motherhood, and broken down by her mother-in-laws criticism of her “laziness”. When women‘s voices are not heard, their bodies translate their distress to bodily pain, an S.O.S. less easily ignored in an agricultural community. Conscious of this phenomenon or not, they arrive at our clinic seeking a dose of compassion and prescribed rest. Others resort to a louder form of protest and reclamation of power: in recent years there have been a number of young female suicides in our clinic’s community.

In parts of Nepal, girls are withdrawn from school at menarche to marry a boy that they have never laid eyes on. There is often little courtship before marriage, with the expectation that brides be both young and virginal. Arriving in a new home, naive and possibly illiterate, they become housekeepers, caretakers, and mothers. Their young husbands may soon be displaced too, sent to the Persian Gulf to earn money in construction. Both sexes are vulnerable to exploitation abroad, whether as laborers or sex workers.

Under this myriad of pressures and threats, it is easy to imagine how one partner’s withdrawal from their functional unit, with no way to break the union, could escalate to violence. We are reminded, before entering the clinic, to be alert for signs of spousal abuse. Unfortunately, we have little to offer victims of domestic violence. There are no women’s shelters in rural Nepal. Divorce is the loss of your children and disgraceful return to your parents' home — the street if they will not take you. There are few women for which this is viable.

With these women’s stories in mind, I see my American grocer’s towering shelf of honey in a new light. Growing up in white suburbia, many of my peers were paralyzed by their parents coos: “you can be anything you want to be… you’re a star.” Their fourth grade recorder recitals were met with an applause louder than the squeaks of their tiny fingers failing to plug their instruments’ holes. Under the pressure of infinite possibilities and implication of great expectations, it seems impossible to succeed. With their eyes scanning the horizon for the tallest peak, their anxiety blinds them to the gift that is the solid ground beneath them. Choice begins to feel like a trap, and many unhappily rebuke the accusation that they hold privilege.

Whereas an American might wish for certainty and stability, Nepali girls are shown the way. One might envy this prescribed path, but, if it leads them into a pit, there is no escape rope. In America, many women find themselves similarly bound, by economic or social constraints. This bind is not uniquely Nepali — all over the world, women and femmes are subjected to patriarchy’s injustices. For those who have choices, however, it is our task to cultivate the certainty and stability in ourselves to navigate them. Instead of throwing our arms in the air, we must weild our privilege as a tool to raise ourselves and those around us. This does not mean pitying those whose voices are being suppressed, but rather placing our speakerphone to their lips, so that they may make their choice. Recruit others. Speak their truth.

On the side of the road, my lap cradles a teenage girl’s head, tears tumbling down her cheeks. After fainting, desperately attempting to convey how she was hit by the motorcycle that left her covered in dust and curled over in pain, she has just regained consciousness. Her hands are stiff and her heart is beating like a little bird in a cage. Though physically stable, her foundation is shaken.

Men arrive at the scene: some curious, some concerned, and others called upon. All seem to launch into their own theater. Her brother’s friends runs to join me in the dust, as though he has come upon his Juliet, her lips tainted by poison. Behind him, her brother looks like he is posing for an emo album cover, flipping his slick hair and seemingly disengaged. A man with a lazy, plastic eye is yelling at her for details of the motorcyclist’s identity and direction, pacing as he wildly gesticulates, like a Nepali Sherlock Holmes. The ambulance driver, who looks more like a former World Wide Wrestling contendant, is standing with his arms crossed, discussing the scene with one of our Nepali staff, occasionally glancing at his soon-to-be passenger.

I quietly stroke her head, occasionally asking our interpreter to remind her to breathe: her greatest responsibility in this moment. Feeling her surrender the weight of her head to me, I hope that she can reclaim herself from this moment. I wonder if she feels supported or stamped out by the men around her. Does she identify with any of their performances? Does she feel like a Juliet, emo dreamgirl, or chalk outline? Is she conjuring images of powerful women like a mother, Rihanna, or Laxmi? I watch these men take her from my lap, her impression leaving me numb from the knees down and caked in dust.

Nepal has made great strides in the past couple decades. Despite the mysterious massacre of their royal family, coup by guerilla warfare, struggles with corruption and economic poverty, devastation by the 2015 earthquake, and challenging terrain, the country is developing in leaps and bounds. Though not always enforced, measures have been adopted into the Nepali constitution to protect women and girls. There are incentives for young women to stay in school, defining their identities before merging with another’s.

Pins and needles seize my ankles as the girl who nested in my lap is settled into the ambulance. I do not know what the future will look like for her and nor do not look down on her, or any of my patients. I am inspired by Nepali women’s tenacity, enthusiasm, and cheer. Each time I search for their vertebrae beneath the thick bands of muscle flanking their spines, I feel immense respect for all that they carry and contain. I am humbled that they entrust me with their bodies, their pain. It is my greatest motivation to be a better practitioner, to show up for these women as they do for their families. --- Beth Randles