I’m totally overdressed, now sweating in my puffy jacket that only a few hours ago seemed totally adequate to stave off the morning frost. The Nepali middle hills tower and surround my small team of companions as we examine a man whom we came to see. The small, thirty to forty square foot shed made of corrugated sheet metal that is cobbled together with wire, serves as a house for him and his wife. It becomes our backdrop as we sit on a blue plastic tarp spread over the dusty, hard-packed ground. The stench of gangrene burns my nostrils and I am thankful for the thin latex barrier provided by my examination gloves as I probe the bone deep wounds on his feet. His three goats and a small mangy black and white dog look on at the strange scene with indifference.

Just an hour earlier, I was witness to one of the loneliest human beings I have ever encountered. About a two hour hilly and steep walk from our Bajrabarahi Clinic -- basically two valleys over-- lays a small settlement of about a dozen stone and mud houses. Some have traditional thatch roofs, where others have a mixture of terracotta tiles and newer corrugated metal. A small creek supplies water to a population of about fifty Tamang people. The Tamang people may have been the original inhabitant of the Kathmandu valley originating from Mongolian tribes who migrated through northern Tibet into Nepal. Today they remain a very isolated ethnic group maintaining their own language and customs, rarely intermarrying with other ethnic groups. Typically they are very superstitious with a healthy skepticism of foreigners and have a higher than average poverty and illiteracy rates-- especially in these more isolated areas.

A visiting allopathic doctor from the United States and I have been brought here to see a woman who has an “eye problem”. When we arrive at her house it is a tiny structure set well away from the main settlement. It is overgrown by large vines, which are barren in early December. When the woman emerges from her house we see that she is an albino. It is difficult to determine her age because she shields her face with several scarves to protect her skin and eyes from the bright sunlight. (Later it is revealed that she is in her early forties.) Because of her albinism she has been shunned by the rest of the community. She is unmarried, alone and mostly blind. We examine a crusty and cracked lesion about the size of a walnut on her left cheek bone which has also invaded her lower eyelid. “It’s painful,” she tells us with voice so soft it is almost inaudible. Our suspicion is that we are looking at a basal cell carcinoma, a type of skin cancer. She has never in her life left this valley and I am certain that she could not even begin to imagine the complexity of Kathmandu. Additionally, on her small plot of land, she barely scratches out her own survival and would have no way of affording the transportation to the capital, let alone the medical care that would be needed. Even more of an obstacle than the basic resources would be the lack of family/community support to help manage her care and recovery.

Nepalis respond to this kind of encounter with the phrase “Ke garne (kay gar-nay)”. Roughly translated it means, “What to do?” It’s basically a language equivalent of shrugging your shoulders and throwing up your hands. It means that there is no solution so we should just move on.

The Nepal experience is impossible to summarize; filled with simultaneous breathtaking beauty and heart wrenching human drama. The sights, smells, people, countryside and cityscapes are so foreign to our western sensibilities; they blur into an indescribably complex mental and emotional collage. I have been traveling in Nepal for two decades now and practicing medicine the best I know how in rural areas for eleven of those twenty years. The Nepal experience has been woven into the fabric of my soul in a way that creates a completely unique tapestry-- the threads of which find their origins in moments like these.

The exact circumstances that have brought me to this village today originated almost three years ago. Since beginning this project in 2008, I have faced off with a mountain of unassailable medical and logistical challenges, mostly revolving around the same question: how do I help people who are so far from proper medical evaluation and treatment that also lack even the most basic resources and education? Spend one day in our clinic and you will see everything from babies to centenarians; pain from worn out joints burdened by years of heavy lifting and agricultural work; Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) from cooking over wood-burning stoves in unventilated kitchens; hypertension often coupled with diabetes leading to a very high rate of stroke and heart attack; stubborn ear infections resistant to conventional treatments because of antibiotic overuse, often resulting in permanent hearing loss. And this is the easy stuff! We also see cases of tuberculosis in which we struggle to find the right combination of resources to secure a proper diagnosis and treatment. Patients with cancer, pneumonia, leprosy, birth defects, mental illness, alcohol abuse, domestic violence-- and today, gangrene. This is what we do. Assess and manage conditions, which we are able to within our clinic, and try to find solutions and resources for conditions that we can’t manage.

Three years ago I had the opportunity to speak to a panel of government officials at the Makawanpur District Health Office. Every organization working in the health sector within the district was asked to give a short presentation about their work. We presented our work alongside several global organizations like UNICEF, Save the Children and the World Health Organization. I recognized that this was both an honor and an opportunity. What I had to say began a small trickle of new thought that I hope will later supply a waterfall of innovative reform in how rural healthcare can be delivered in Nepal.

Like most developing countries, Nepal is in transition. In the past, infectious diseases like influenza, typhoid, cholera, polio and measles were the biggest threat to life expectancy. Now however, a new category of non-communicable (sometimes called “lifestyle”) diseases (NCDs) have surpassed infectious diseases in their impact on mortality and costs to the health care system. Diseases like chronic pain, COPD, hypertension and diabetes not only shorten life spans but they also dramatically lower an individual’s quality of life and they are incredibly costly to manage, often resulting in many complications, hospitalizations and specialized care. From a public health standpoint, as I said in my presentation, “You cannot medicate your way out of these problems.” Once a person has diabetes or COPD, generally there is no way back; it will require medical management from this point forward. Yet, global funding in the health sector has not caught up with this idea. Most of the organizations presenting that day were stuck in fantastically expensive programs focusing on infectious diseases that were affecting fewer and fewer people.

“We have to figure out how to prevent the next stroke, the next diabetic and the next breathing disorder. We first have to know which diseases are of the most importance, we need to know how to best prevent them, and we need to fund programs that will change long term disease progression and medical outcomes. Most importantly, we need to know that our programs have actually achieved that goal. We need to begin with a large-scale baseline study of the prevalence of NCDs in our areas of operation. This will identify areas of greatest impact in which the most effort should be applied.” This presentation launched the next chapter in our organizational focus and began a new partnership with the District Health Office and local health officials.

Much research has been done on the management of NCDs in other countries and the World Health Organization has published many guidelines for the establishment of “lifestyle” clinics but nothing has been done in Nepal. After that meeting, I spent several hundred hours reading research and collaborating with other researchers to develop a baseline study that could be replicated across Nepal. I received critical writing support and expertise from Ben Marx and Deborah Espesete at the Oregon College of Oriental Medicine. They helped me fine tune the questionnaires and provided critical facilitation of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval process. This last step is an international requirement for doing research on human subjects.

Last year, I spent much of my time in Nepal seeking the approval for this study of the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) and the District Government which we received in late 2017. Pivotal assistance in this process was provided by Mr. Bimsagar Guragain. Bimsagar is the Health Inspector for the Makwanpur District Health Office and has been an active advocate for the development of “lifestyle” medicine in Nepal. He has been an enthusiastic supporter of our work and serves on the Board of Directors of our domestic non-governmental organization (NGO), Suswasthya Nepal (Good Health Nepal).

One of the most gratifying parts of my job is finding and empowering young Nepalis to step up into leadership roles and this year we had two new additions to our team. (I’ll talk about the second, our lab technician Anupa, in a separate post.)

When I arrived in Nepal this year I was introduced to a bright young woman named Renuka Suwal. She had been trained as a physiotherapist in India but was interested in work in public health as a researcher. Over the last couple of years, Renuka had been freelancing as a data-collector but was now looking for an opportunity to lead a research team. I was very impressed by her professionalism, so we hired her as our Research Director for the purpose of executing the field portion of our survey.

All of the elements were beginning to align, however, before we could go into the field, we had two more important hurdles to cross. First was to have a formal meeting with the Mayor of Thaha Municipality and other local community leaders. This was a critical opportunity for us to not only attain final permission to go forward on our research project but also to take advantage of this influential audience. (In Nepal, it is typical that you have to pay-- and feed-- government officials for them to attend your presentation. It was a significant investment on our part but worth it to have a captive audience for two hours. We just needed to make it count.)

We wanted to talk about the research, but I also wanted to communicate our plans to develop an integrated “lifestyle” medicine center unlike anything seen in Nepal. We were asking for their support in dramatically increasing our scope of practice and medical authority-- something we have been trying to do for several years. It was in this meeting that I saw Renuka really shine.

Renuka is a modern Nepali woman, educated and informed. At twenty four years old, wearing a well-tailored power suit rather than a traditional sari, she made a very persuasive presentation to the Mayor. Most remarkably, about midway through the meeting, the politicians got sidetracked and were running amuck with a loudly debated subtopic. Renuka calmly but firmly told them that there would be plenty of time for interaction at the end of her presentation but they needed to hear everything she was there to say. Shockingly, they complied and she carried on uninterrupted. (I knew we had made the right decision in hiring her!) We came out of the meeting with everything we had hoped to receive.

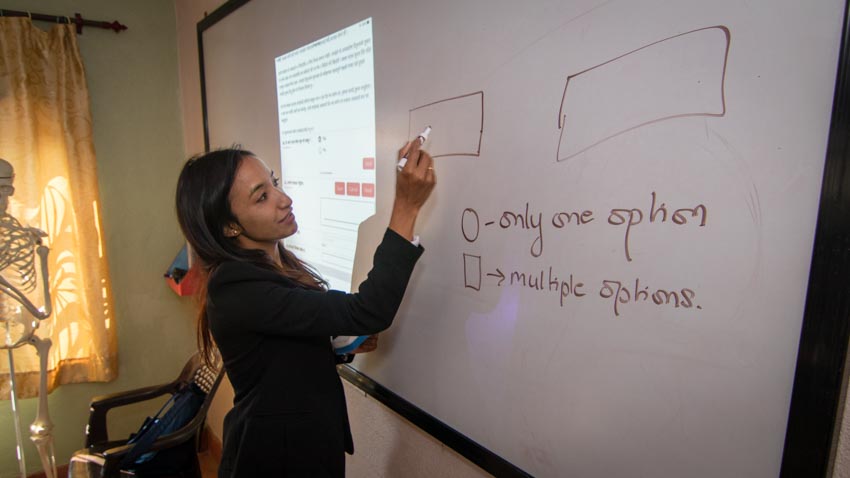

Our second hurdle was recruiting and training data-collectors. We tapped into people that we already had some experience with-- our past and current interpreting staff and acupuncture students that we were sponsoring. We hired ten of them to come to Bajrabarahi for six weeks. During the first week they had to learn how to accurately take seven biometric measures: blood pressure, blood glucose, respiration rate, heart rate, oxygen saturation, hip circumference and waist circumference. They also had to familiarize themselves with our two survey tools; one for head of households and one for individuals. (Each of these surveys has over three hundred data points which need to be assessed.) Lastly they had to learn how to use our Android tablets and RedCap software to administer the surveys. They practiced and practiced. They asked questions and clarified the meaning of certain question and after five days we felt we were ready to go into the field.

Our task was to do a door to door survey of what we consider to be our primary catchment area-- the area in which ninety percent of our patients come from. It is about fifteen square miles of steep hills and sparsely scattered farms of terraced fields. We hoped to survey roughly fifteen hundred households and three to four thousand individuals in five weeks.

What I saw in the following weeks put the biggest smile on my face: sharply dressed data-collectors sitting in the fields or outside of peoples homes, usually sitting amongst the goats and water buffalo, as all of the neighbors gathered around to listen and watch. Our crew asked people about their health and administered a simple health checkup. Anyone with suspect vital signs or other health concerns was given a referral slip which they could bring directly to our clinic. Since houses in Nepal do not have addresses we needed a way to mark those that had been surveyed. We came up with stickers that were sequentially numbered and had ten health tips printed on them. By applying these to the doors of the houses, we had essentially “addressed” the entire village with a house number.

Many of the villages where hard to reach, requiring one to two hours of serious effort by walking. Our researchers would have to leave very early in the morning and would often not return until after dark. As they reached more distant villages, we began to discover more serious health issues. With less access to health facilities and a general lack of education, we began to see more and more unmanaged conditions. It became very apparent that we need to be prioritizing more outreach efforts in the future.

People were so happy to see us, often offering our team members tea or snacks along the way. They were very curious to have their blood pressure checked and in order to consent to our survey, they had to sign their name using their finger on the tablet. (You have probably done this yourself at your local coffee shop.) They were delighted!

It is too early to say what the data shows or means. That will take several more months of analysis. However, I’ll share a few insights. More than fourteen percent of the population have signs of stage two or greater hypertension. Sixty percent of households still cook with wood. Of those households, less than ten percent have any kind of ventilation for smoke in their kitchen. About twenty percent of the population had visited our clinic at some point and about half of them said that our care was either curative or significantly helpful.

That being said, let me get back to our man with the gangrene on his foot. Not to be too gruesome about it, but I could clearly see the bones of his ankle through what was left of his flesh. (The stench was unforgettable.) He needed immediate help in the way of an infectious disease specialist and that would mean transportation and hospital care. The down side of this is that we know he is probably facing an amputation of both feet. Look at it from the man’s perspective--one day two foreigners show up and then my feet get cut off! This isn’t going to go well for us.

Now that you have read this far, I feel sad that I’m not going to be able to deliver a happy ending; instead you will have to bear with a seemingly ambiguous and unsatisfactory ending to the story. But this ending illustrates exactly what we struggle with everyday and hopefully will help me make my point. Here goes.

We carefully explain to the man what is wrong with his feet and that he needs to go to the hospital. We will help him by arranging transportation and free treatment at the National Leprosy Hospital. All he has to do is agree to go. After some discussion, he agrees and we make plans to transport him the next day. All seems good in the world. We think, “Mission accomplished!” as we head back to the clinic.

The next day my coordinator, Tsering Sherpa, and I head out to the village by motorbike to make final preparations. The ambulance we had arranged was on its way. When we arrive at the house, the man was not at home. His wife says to us, “He already went to Kathmandu. He left at 4:00am”. That was very unlikely, because he could hardly walk and he had never been to Kathmandu in his whole life. We decide to ask his neighbor. They say, “I just saw him. He went that way!” and they point. Not knowing what else to do, Tsering and I make our way back to the motorbikes. We are parked up on a ridge and we can see down to the man’s house. About fifteen minutes later we see him pop out of the bushes and return to his house. It’s obvious that he has no intention of going to Kathmandu today-- or ever. I decided that my presence may be making things worse, so I instruct Tsering to go talk with the man by himself. I tell Tsering, “I can understand why the man is afraid. It is very likely he will need an amputation, however-- the man will likely die without it and he needs to know that. Please convey our concern and ask him if he will accept our help.” Tsering returns to the man’s home, only this time, the man does not run away. Instead, Tsering is met with hostility, wherein the man insists that Tsering is trying to take advantage of him and that he is being forced against his will. He makes such a fuss that his neighbors soon respond with farm implements to chase Tsering away. Tsering sensing that he may be in danger, departs and we ride away… Ke garne.

I consider this a medical failure. The best medicine in the world cannot help if you cannot establish trust. But how can we establish that trust if we are strangers?

From this experience, I have asked the District to help us coordinate a regular outreach program in which Nepali doctors and medical students can come to the field with us once a month or so. Not to solve problems, but rather to better understand them. And, hopefully to cultivate a constructive conversation about collaborative solutions. Most of all, I hope that by showing our faces in some of these remote places it will help us be less strange. Maybe if we can sit and have tea together, we can understand each others needs and learn to trust each other.

Don’t despair-- not all of our cases go this way and we significantly help many people. Just this month I watched a volunteer practitioner help a woman in her mid forties who had suffered a stroke. The volunteer had been working so hard on this case and one day the woman was suddenly able to wiggle her thumb which hadn’t moved in several years. This was a small but significant step in the recovery of a paralyzed limb but in this moment-- this woman whose body is severely disabled, who drags her foot as she manages the hour long walk to the clinic everyday-- this woman suddenly has hope. Additionally, at our Tistung clinic we screened three young girls who had significant hearing loss. In this case we were able to get them to an audiologist in Kathmandu. One of them received a reparative surgical procedure which restored about seventy five percent of her hearing and the other two received hearing aid devices. These interventions will allow them to better participate in school. Then there was the man with the inoperable hip fracture who is now able to walk again without a cane. There are so many.

And, as for the albino woman with the skin cancer: I haven’t given up. My team and I have been consulting with hospitals and specialists searching for the right solution. We plan to make several visits to her house to establish a better relationship before we try to “help”. I think that the simple fact that we make the effort to visit and to show some authentic concern for her well- being may relieve some of her loneliness. That may turn out to be the best medicine of all.

Author: Andrew Schlabach, MAcOM EAMP

Director, Acupuncture Relief Project

Bajrabarahi, Thaha, Makawanpur Nepal