One brisk morning in Makawanpur, as our team was finishing breakfast and preparing to head over to the clinic, a man stopped by to ask us if we could have a look as his mother. The man is a carpenter who has been helping us with our new clinic building and the weary expression on his face speaks volumes as to what might be going on with his mother. I grab one of our mobile kits and ask one of the other practitioners and an interpreter to come with me up to the carpenter’s village.

As part of my work in Nepal, I really enjoy visiting patients’ homes and doing house calls. Too often we don't have time or the resources to spend walking out to neighboring villages, but when we do, I always find the experience enriching and illuminating. For example, a couple of weeks ago I was returning from a house call when I was stopped in the street by another patient who asked if I could look at her mother. She told me that her mother had suffered a stroke more than a year ago. When I went to their home and saw her mother however, I quickly realized that her mom had not suffered a stroke, rather she was in the advanced stages of Huntington’s Disease. On my walks, I find many disabled, paralyzed and elderly people; I also get acquainted with the village drunks. Sometimes I discover a few cases of mental illness and birth defects lurking in the population. All of these conditions exist everywhere in the world, it’s just that we rarely get to see them all in one place. That is the beauty and nature of working in a village; our patients are everywhere. They vigorously greet us in the street, offering tea or food while giving us updates on their progress and interest in acupuncture. “Ma Dhukdhana! (I don’t have any pain)” an elderly Tamang man shouts while pointing to his knees and throwing his walking stick to the ground. “Deri Ramro! (Excellent!)” I reply while giving him a thumbs up sign. (I have no idea what that gesture might mean in Nepali but it usually makes people laugh.)

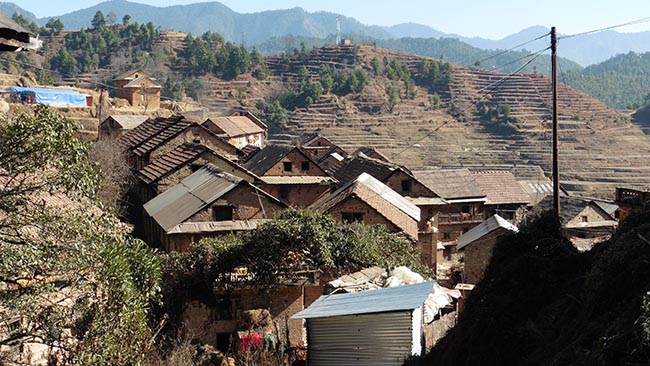

On this particular day, it takes us about 45 minutes to walk a few kilometers into the hills just to the west of our clinic. Small, two story, stone and mud houses are clustered tightly together along the hillside in this old Newari village. The Newar heritage can be seen in the intricate wood carvings around the windows and the sweeping uplifted corners of the rooflines. It looks like a 14th century movie set save for a few sad-looking satellite dishes and the modern water tanks. The road is so steep and rocky it’s only passable on foot, and yet, I see two decrepit motorbikes parked about midway up the hill. In most of these houses cows, water buffalo, goats and chickens are kept on the ground floor with the family living upstairs. The air is thick and stings my nostrils with the acrid wood smoke of cooking fires. Evidence of the recent earthquake can be seen everywhere with collapsed roofs, cracked walls and sometimes completely destroyed buildings. On the other hand, there are what appear to be centuries old buildings standing completely unaffected. Damage aside, there is no doubt that life goes on as the village is abuzz with everyday activities. A woman who looks to be at least 150 years old, offers for us to drink rakishi (local distilled alcohol) with her. We happily decline, as it is only 9:00 AM, and wish her a good day.

In the villages of Nepal, people do not live inside their houses. The house is really just for storage and sleeping with very small living spaces and low ceilings. Creosote coats the walls and roof beams from years of cooking fires and the smell of livestock, mold and dust permeates the air. Most daily life takes place in the small courtyard in front of the house. This is where meals are prepared, laundry is washed, crops are dried and where neighbors gather to socialize while they work. Thusly it was no surprise that when we arrived at the carpenter’s house, his extended family (about 12 people) were all gathered in this outdoor space enjoying the morning warmth from the sun and busy with their daily chores. On a hand woven grass mat in the middle of all of this activity, two younger women support and offer a cup of water to a woman who appears close to death.

I take a deep breath to calm my mind and offer a silent prayer. “Steady,” I think as I look to my assistants. Then we begin. Make contact, exam, vital signs- is the patient lucid? Barely. My interpreter and I listen to the family members tell their story and we ask many questions. Bit by bit we slowly begin to understand the situation.

The woman is nearly 80 years old (in Nepal, elderly people do not know their exact age as they do not celebrate birthdays and they do not have any government issued birth documents.) She is as thin and frail as you can image a person to be. Her daughter-in-law claims she weighs less than a sack of rice (40kg or 80-90 lbs). When we try to take her blood pressure, her upper arm is less than one inch in diameter and even our smallest cuff will not fit her. Her vital signs are so weak they are almost imperceptible. Her abdomen is distended and tender. Every bone in her body is visible through her thin and dehydrated skin. Cancer? Internal bleeding? She is in some discomfort but not in agony and periodically she speaks a few words, usually asking to be moved to a different position. “Sit me up,” she says, then after a few minutes “Lay me down.” She has been this way for 5 weeks, gradually declining. She has not eaten in three days and she is only drinking a few sips of water now and then.

I look around and take in the scene. “How many people are here?” I think. 10? 20? 30? Family? Neighbors? Every one fascinated by the activity; all looking to us for answers. I look at the carpenter, his weathered face with deep crows feet accenting his high cheekbones. In his eyes I see the question, “What do I do?”

Who is my patient? The woman who is dying or carpenter or the whole family… maybe the whole village?

Of course if I was in the U.S., I would just dial 911 and, like magic, a team of paramedics would materialize within a few minutes, whisking her away to the lifesaving miracles of modern medicine. I wouldn’t even give the slightest thought to how much that might cost. But here… the nearest hospital is 4-5 hours away by kidney-busting roads. Even if she survived the ambulance ride (I use the term ambulance loosely because it is just a four wheel drive truck with a flashing light and lacks any medical equipment or trained personnel) what hospital would we send her to? What can the family afford? If the patient is put on a respirator she could easily drain the family’s resources beyond their basic survivability.

What to do? How can I possibly answer this question for everyone.... Here is the reality. Like it or not, I am the senior trained medical provider in this village. This family is asking for my professional opinion, on which they will base their plan of action. “What is best?” I ponder. What advice will relieve the maximum suffering? What is ethical?

I begin by clearly stating what is happening. I look the carpenter in the eye, take a long pause, and say… “Your mother is dying.” I go on to explain that I do not believe there is any medicine that will prevent this from happening and that it will likely happen soon. I tell him that she is in some pain and that the hospital would be able to give her medicine to relieve that pain but it is unlikely they will prevent her from dying. It is my opinion that the ambulance transfer to the hospital will be very stressful and possibly fatal for her. It is my sincere feeling that she would be better off in the care and surroundings of her home and family. I empathize that it is a difficult but necessary choice he would have to make for himself, his mother and his family. Under the clear blue sky, surrounded by his extended family and neighbors, the carpenter received this news with stoic silence. He began to cry a little and then he said, “Thank you”.

What came next was an amazing sigh of relief. Everyone gathered there suddenly knew exactly what to do: make Ahma (grandmother) comfortable. They ask lots of questions. We show them how to keep her bedsores clean and advise them to change her clothing and bedding daily. We show them how to massage her dry skin with mustard oil and we explain that she needs to be out in the sunlight and with the family as much as possible. “Don’t leave her indoors, alone in the dark during the day. Hold her hand and speak with her even if she can not speak back to you.”

We left them saying that if her condition changes or if they felt her pain was becoming intolerable, “Just call us and we will come.”

The day after our visit the woman sat up on her own and asked to sit in the courtyard with the other women while they worked. She sat all day in the sun and sipped tea. This was the first time she had sat up under her own power for over a month. The women asked her what she was thinking about; sometimes she would reply and sometimes just sit quietly. That night she passed away in her sleep.

With every decision I have to make there is a consequence. I don’t alway get it right. Many of you might think that I made a poor decision in this case. You may be right. As much as I try to understand what is “best” for a patient, I never really know the answer. What I do understand is that every day our practitioners go to the clinic and try to palliate life. With simple acupuncture and herbal medicine we reduce pain and alleviate many conditions, helping people return to work and to the care of their families. With our assessment and diagnostic skills we help people access and understand the care they need, often guiding the treatment of other physicians. All the while we are working on those aches, pains and injuries that rural living delivers to the body, we’re getting to know our community. We are diligently surveilling for tuberculosis, cancer, hypertension, respiratory dysfunctions and infectious diseases- constantly scanning for signs of mental illness, depression, domestic violence and substance abuse. Maybe our treatment is just the context in which we relate to our patients and community. I can live with that.

Patients often tell me, “I’m afraid to ask my doctor a question.” In Nepal especially, questioning a doctor will likely earn you a prompt scolding. This fact really breaks my heart. Doctors rarely, if ever, offer a diagnosis or explain the drugs or procedures they are giving to the patient- even to us- and we ask. Illiterate patients (most of our villagers who’re over 50 years old) are totally at the mercy of the medical institutions and they are often frivolously over-treated and overcharged. When I end a patient visit with the query, “Do you have any questions for me?” my patients are stunned. How can such a simple concept go overlooked? Just like the carpenter and his mother, when we take the time to explain what is going on and what can be expected it make all the difference because it enables patients to make their own choices. If nothing else, hopefully through our example here in Makawanpur and through the students that we train, we can begin to get this idea into practice.

In the end, I’m not all that interested in what acupuncture (or any other medicine) can cure. For me it is enough to just struggle with the question, “What is best for this patient?” and to give my utmost effort to provide practical solutions and compassionate care.

Author: Andrew Schlabach, MAcOM EAMP

Director, Acupuncture Relief Project

Bhimphedi, Makawanpur, Nepal