VOLUNTEER COMMUNITY CARE CLINICS IN NEPAL

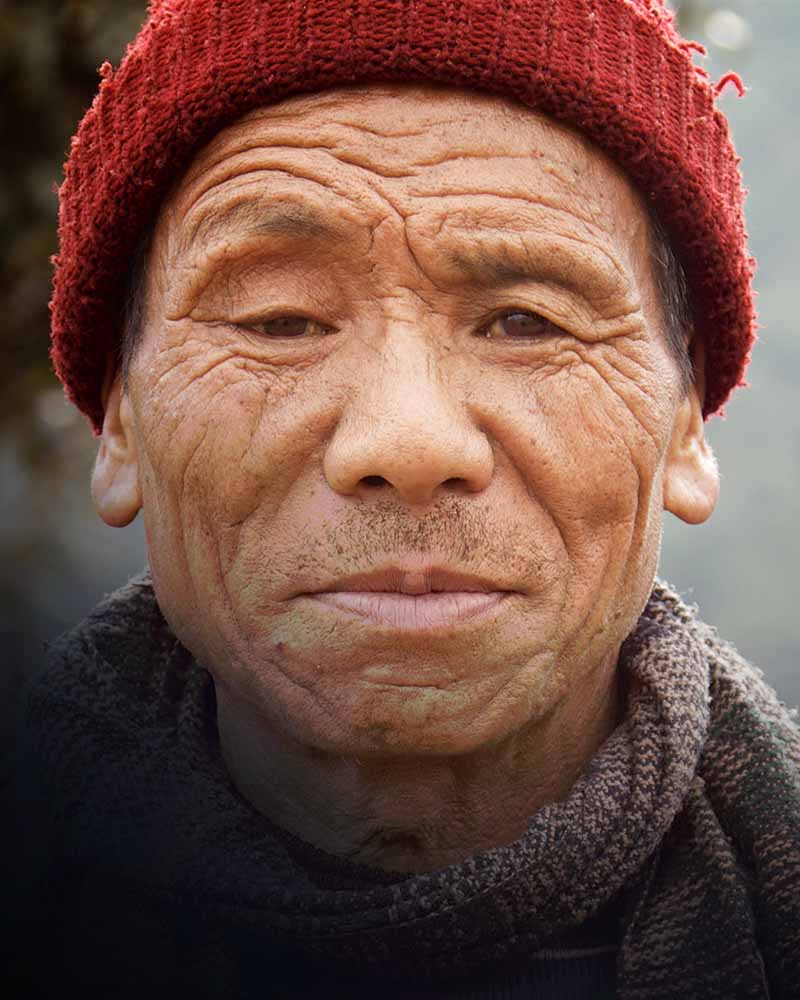

Nepal remains one of the poorest countries in the world and has been plagued with political unrest and military conflict for the past decade. In 2015, a pair of major earthquakes devastated this small and fragile country.

Since 2008, the Acupuncture Relief Project has provided over 300,000 treatments to patients living in rural villages outside of Kathmandu Nepal. Our efforts include the treatment of patients living without access to modern medical care as well as people suffering from extreme poverty, substance abuse and social disfranchisement.

Common conditions include musculoskeletal pain, digestive pain, hypertension, diabetes, stroke rehabilitation, uterine prolapse, asthma, and recovery from tuberculosis treatment, typhoid fever, and surgery.

FEATURED CASE STUDIES

Rheumatoid Arthritis +

35-year-old female presents with multiple bilateral joint pain beginning 18 months previously and had received a diagnosis of…

Autism Spectrum Disorder +

20-year-old male patient presents with decreased mental capacity, which his mother states has been present since birth. He…

Spinal Trauma Sequelae with Osteoarthritis of Right Knee +

60-year-old female presents with spinal trauma sequela consisting of constant mid- to high grade pain and restricted flexion…

Chronic Vomiting +

80-year-old male presents with vomiting 20 minutes after each meal for 2 years. At the time of initial…

COMPASSION CONNECT : DOCUMENTARY SERIES

Episode 1

Rural Primary Care

In the aftermath of the 2015 Gorkha Earthquake, this episode explores the challenges of providing basic medical access for people living in rural areas.

Episode 2

Integrated Medicine

Acupuncture Relief Project tackles complicated medical cases through accurate assessment and the cooperation of both governmental and non-governmental agencies.

Episode 3

Working With The Government

Cooperation with the local government yields a unique opportunities to establish a new integrated medicine outpost in Bajra Barahi, Makawanpur, Nepal.

Episode 4

Case Management

Complicated medical cases require extraordinary effort. This episode follows 4-year-old Sushmita in her battle with tuberculosis.

Episode 5

Sober Recovery

Drug and alcohol abuse is a constant issue in both rural and urban areas of Nepal. Local customs and few treatment facilities prove difficult obstacles.

Episode 6

The Interpreters

Interpreters help make a critical connection between patients and practitioners. This episode explores the people that make our medicine possible and what it takes to do the job.

Episode 7

Future Doctors of Nepal

This episode looks at the people and the process of creating a new generation of Nepali rural health providers.

Compassion Connects

2012 Pilot Episode

In this 2011, documentary, Film-maker Tristan Stoch successfully illustrates many of the complexities of providing primary medical care in a third world environment.

From Our Blog

Like a Miracle

- Details

- By Andrew Schlabach

Preus reaches down to pick up a piece of candy that he dropped with his left hand. Remarkable.

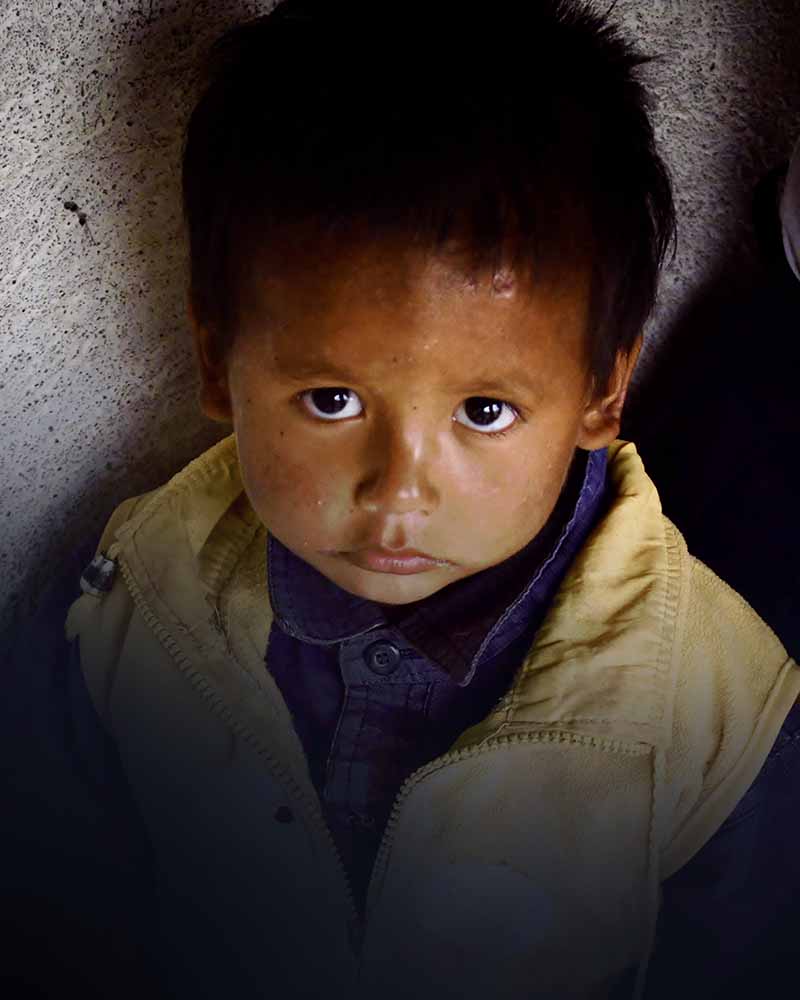

I’ve never met Preus (pray-oos) before but I feel like I have. The COVID crisis taught us a lot about working remotely and through the miracle of Zoom, I had consulted with my team in Nepal about this boy many times. Preus, now 9 years old, was brought to our clinic by his mother in late 2020. The story she told us lacked critical details though we were able to deduce that Preus had suffered a brain injury. On further questioning we learned that Preus had been a normal little boy until about age five when he suddenly became ill with a very high fever which lasted several days. This fever could have been caused by COVID but it was more likely to have been caused by Typhoid (which is endemic in Nepal).

This morning Satyamohan (our senior clinician and clinic manager) and I decided to check in on Preus as he had not been back to the clinic for several months despite several calls to his mother asking for a follow-up. I never pass up a chance to visit patients at home if that is an option. It’s only about a 20 minute motorbike ride up the slippery, steep and rocky road just above our clinic but in some ways, it is a world away. Preus’ family are Tamang, a sub ethnic group found in the hill and mountain regions of Nepal. They maintain their own language, customs and rarely marry outside of their ethnic group. We arrive in the small Tamang settlement made up of about a dozen small, mud and stone, houses with corrugated metal roofs. Several children in dirty clothes gape open mouthed at me (a tall, white haired foreigner on a motorbike) bumping up the road to Preus’ house where we were greeted by his mother. She was just returning from the market, walking down the steep hill above their house wearing flip-flops and carrying a recycled 2-liter bottle of a milky liquid. Chaang is a home-made beer made from rice and other grains. A staple food of hill farmers, its low alcohol content keeps it from growing bacteria while being calorie rich to provide energy throughout the day.

Our Mission

Acupuncture Relief Project, Inc. is a volunteer-based, 501(c)3 non-profit organization (Tax ID: 26-3335265). Our mission is to provide free medical support to those affected by poverty, conflict or disaster while offering an educationally meaningful experience to influence the professional development and personal growth of compassionate medical practitioners.