108 butter candle blessing for our Bajrabarahi Clinic's 10th anniversary, Dec 6th 2025.

Writing has always been a useful discipline for me. It serves as a way to order experience, to work methodically through the collage of thoughts, impressions, and moments that accumulate over time. This has been especially true in relation to my work in Nepal. Since beginning this project in 2008—now more than eighteen years ago—I have worked alongside hundreds of volunteers and treated thousands of patients. More importantly, I have had the privilege of helping cultivate a group of deeply committed and capable health workers.

Taken individually, most of these experiences are not particularly remarkable. They are small clinical encounters, ordinary conversations, incremental improvements, and occasional frustrations. Yet when viewed with sufficient distance, they form a complex tapestry, interwoven with different colors and textures that reflect a sustained and collective effort over time. It is only by stepping back that I can appreciate the coherence and quiet beauty of this work, and recognize it as part of what I would describe as an intentionally lived and inspired life.

Mentorship as Clinical Infrastructure

Before I arrived in Nepal this year, I joined a video call with our clinic team and my colleague, Dr. Bex Groebner. Over the past year, Bex has been working closely with the practitioners to strengthen their case reporting and clinical reasoning. The focus has been on slowing down, describing findings more precisely, and noticing where familiar conclusions sometimes stand in for deeper analysis. It has been a demanding process, but a productive one. The team’s clinical thinking has become clearer, more confident, and more deliberate.

One case in particular stayed with me.

Digish

An eleven-year-old boy, Digish, came to the clinic with long-standing difficulty using his right arm. His family reported that the problem became noticeable around the age of two, following a serious illness with high fever. Given that history—and because we have seen many similar cases over the years—the team reasonably concluded that this was likely the result of a brain injury related to that illness.

What gave me pause were a few details in the case notes. His reflexes were reduced only in the right arm, while the rest of his neurological exam was normal. Strength in the arm was limited, but much of that limitation appeared to come from pain rather than true loss of power. There was clear muscle wasting around the shoulder and shoulder blade, but the forearm was relatively spared. Taken together, these findings suggested a more localized nerve problem rather than a generalized injury to the brain.

Digish at initial examination, September 2025

I raised the possibility that this might represent an injury to the brachial plexus, the network of nerves that supplies the arm, possibly present since birth but not fully apparent until later childhood. We agreed to hold that question open and re-evaluate the case together once I could examine him in person.

When I saw Digish at the clinic, the picture became clearer. His shoulder sagged in a way I often see in patients after stroke, where the joint is no longer well supported by muscle. He could move the arm somewhat, but avoided doing so because movement triggered pain that traveled down the arm. Over time, he had adapted, learning to write with his left hand and limiting use of his right. He struggled with activities like throwing and had begun to disengage at school, describing difficulty with attention and reading, and a growing dislike for being there.

Our understanding shifted. It appeared that the nerves supplying his shoulder were at least partly intact. The larger problem was that years of pain and instability had taught him not to use the arm at all. As a result, the muscles weakened further, and the arm effectively disappeared from his normal movement patterns.

Instead of pushing strength aggressively, we focused on rebuilding trust in the joint. We prioritized exercises where the hand stayed supported, reducing stress on the shoulder while encouraging controlled movement. We used taping to support the joint and acupuncture to reduce pain and stimulate muscle activity. At home, Digish was given simple coordination tasks, like gently tossing a light ball from one hand to the other, to reintroduce movement without fear.

Digish after 3 weeks, November 2025

The change was surprisingly fast. Within a few weeks, Digish rarely complained of pain. He taught himself to juggle two balls. Muscle tone began to return to the arm. His family and teachers reported that he was doing better in school, and Digish himself said he was enjoying learning again in a way he hadn’t before.

His right arm is still weaker than his left. He cannot yet lift heavier weights without compensating through his shoulder, so we deliberately avoided that. Instead, we used simple isometric holds with a partially filled water bottle. At first, he could manage only a few seconds. Within weeks, that time more than doubled.

Digish after 6 weeks of treatment, December 2025

There is still work ahead. Based on his progress so far, I expect that Digish will regain most of the use of his arm over the coming year.

What makes this case meaningful is not just the improvement itself, but what it reflects. It shows how far our team’s clinical reasoning has come, the value of slowing down and questioning assumptions, and the impact of sustained mentorship. It also captures what this clinic does best: careful observation, practical care, and the patience to allow meaningful change to unfold over time.

Holding the Line

Not every case offers clarity or resolution. Some unfold slowly, constrained by uncertainty, limited options, and the boundaries of what we can responsibly do. One such case this year involved a seventy-two-year-old man who was brought to our clinic with profound neurological and medical complexity, and no easy path forward.

He had lived with bipolar disorder for nearly three decades, previously managed with lithium. About fifteen months earlier, his family believed he had suffered a stroke, though he was never formally treated and continued working for some time afterward. Four months ago, his condition worsened: slurred speech, right-sided weakness, and increasing difficulty functioning. He was eventually taken to Kathmandu, treated for lithium toxicity, and found to be in atrial fibrillation. Imaging showed evidence of an ischemic stroke, but the family chose to take him home against medical advice.

To complicate matters further, in Nepal it is common for people to seek medications directly from pharmacists, often without a prescription from a physician. In this case, the man was given risperidone, an antipsychotic medication, without a formal mental health evaluation or structured follow-up. Given his medical and neurological history, this was a particularly concerning development.

When he first presented to our clinic, he was unable to walk. He had weakness in his right arm and leg, constant dizziness, slurred speech, and dangerously elevated blood pressure. The family reported that he had been bedridden for weeks and carried everywhere. Medical records also suggested chronic kidney disease, though details were incomplete. Taken together, this was a fragile situation, marked by overlapping neurological injury, cardiac risk, psychiatric history, and poorly coordinated care.

Acupuncturist Sanita Gopali uses electro stimulation therapy to help with paralysis, 2025.

We were immediately concerned about several things: the use of risperidone without psychiatric supervision, the possibility of ongoing or untreated heart rhythm abnormalities, and the risk of another stroke. We advised hospital referral. The family was reluctant, and that reluctance has persisted.

Over the following weeks, we saw him four more times. Each visit required careful boundary-setting. The family repeatedly asked us to adjust his medications, something we were not willing to do without appropriate specialist evaluation. At the same time, we did what we could responsibly offer. Through acupuncture and supportive care, his blood pressure improved and stabilized. His heart rate became more regular on examination. He began sleeping better and reported feeling more energy.

Perhaps most surprisingly, as we spent more time with him, it became clear that there was no structural reason he could not stand or walk. His inability to do so appeared to be the result of prolonged bedrest and deconditioning rather than irreversible paralysis. With assisted standing and supported walking during clinic visits, he began to regain some confidence and strength. Progress has been slow and incomplete, but real.

Slow but meaningful progress, December 2025

Still, the central concerns remain unresolved. The risperidone continues without specialist oversight. The question of long-term stroke prevention remains unanswered. The family’s hesitation to pursue hospital-based care has not changed.

This case has prompted difficult conversations within our team. Where does responsibility end when patients or families refuse referral? How much improvement risks creating false reassurance? At what point does supportive care become an unintended substitute for definitive evaluation?

Rather than forcing premature solutions, we have focused on clarity. We continue to recommend psychiatric evaluation and are exploring whether a telemedicine consultation might be possible through our referral network. We document carefully, communicate consistently, and avoid crossing lines that could cause harm, even when pressure to “do something more” is strong.

This case may not resolve neatly. It may never offer the kind of outcome that fits easily into a report or a success story. But it reflects another essential function of this clinic: acting as a stabilizing presence, a filter for risk, and a place where careful judgment matters as much as intervention. Sometimes the most important work is not fixing a problem, but holding it responsibly long enough for the next right step to become possible.

Shared Ownership

If the clinic has a future beyond my own presence, it will be because leadership has been allowed to emerge in different forms, at different speeds, and through different paths. This year, that became especially clear through the parallel growth of Sita Bakhrel, Satyamohan Dangol, and Sushila Gurung.

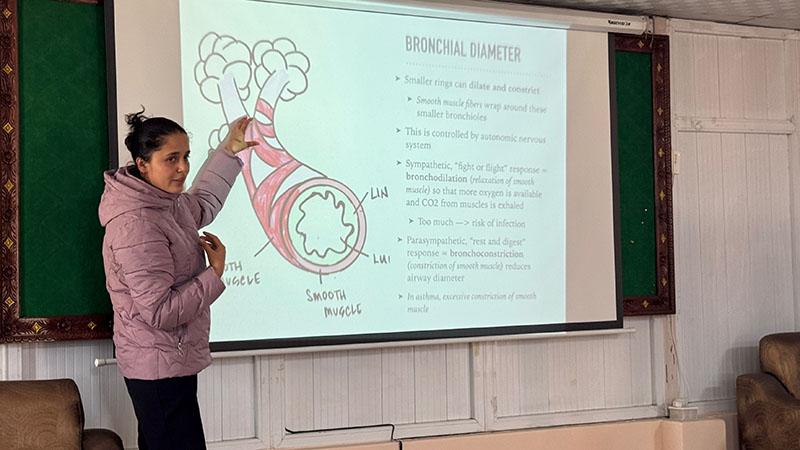

Sita Bakhrel presenting at an Acupuncture Relief Project workshop in 2024.

Sita joined our project first as a student, encountering the clinic not as a destination but as a possibility. In her early years, she was learning fundamentals—how to take a history, how to examine a patient, how to think beyond a single symptom. What stood out even then was her attentiveness. She listened carefully, asked thoughtful questions, and showed a steady curiosity about how health fits into the broader fabric of people’s lives.

Over time, her role expanded. She moved from student to intern, from intern to practitioner, and gradually into leadership. Today, she works clinically while also holding administrative and organizational responsibility. She bridges conversations between local clinicians and international volunteers and helps translate not just language, but expectations. Her growth has been quiet and deliberate, less about stepping forward and more about being consistently reliable.

Satyamohan Dangol demonstrates intra-articular acupuncture for osteoarthritis, Kathmandu 2025.

Satya’s path has been different. He has been with the project since the very beginning and is one of the most skilled clinicians I have ever worked with. His strength has never been visibility. He is deeply humble and instinctively uncomfortable with recognition. And yet, his presence in the clinic is unmistakable. Patients trust him immediately. He has an extraordinary sensitivity to what people need, not just physically but emotionally, and a way of communicating that builds confidence without fanfare. Within the community, he is quietly revered.

Sushila Gurung and her model, Sita Bakhrel, demonstrate a knee examination, 2025.

Sushila entered the project from yet another angle. She began working with us in 2010 as a medical interpreter, helping bridge the gap between visiting clinicians and local patients. This was also how she and Satya met. Over time, she chose to pursue acupuncture training herself, graduating in 2019 and returning to the clinic first as an intern and then as a practitioner. In 2020, we asked her to step into the role of clinic director.

Where Satya is reserved and intuitive, Sushila is organized, articulate, and naturally suited to leadership. She thinks in systems, communicates clearly, and has an educator’s instinct for structure and clarity.

This dynamic was on full display during the three-day workshop I taught in Kathmandu this year, part of an annual program we have run for the past four years. The topic was degenerative bone disease, with a focus on pathology, integrated treatment strategies, and managing co-morbidities. I handled the lecture material, but the practical teaching was led by Sushila and Satya. For both of them, this was their first formal experience teaching peers.

Satyamohan Dangol demonstrates acupuncture for spine degeneration, 2025.

They demonstrated acupuncture protocols using electro-stimulation and guided two practical sessions, supporting participants as they worked through unfamiliar material. Understandably, they were nervous. Standing in front of a room of colleagues is demanding for anyone, and particularly so for someone like Satya, for whom public visibility is deeply uncomfortable. And yet, once the teaching began, both of them settled into their roles with ease. Their colleagues responded with genuine appreciation, not because of polish, but because of clarity, competence, and humility.

Satyamohan, Sushila and Sita answer questions from colleagues and students, 2025.

Sita played a quieter but equally important role during the workshop, coordinating logistics, supporting communication, and helping ensure that the material landed in a way that was practical and relevant for Nepali practitioners. Together, the three of them embodied different aspects of leadership: teaching, organization, clinical depth, and relational intelligence.

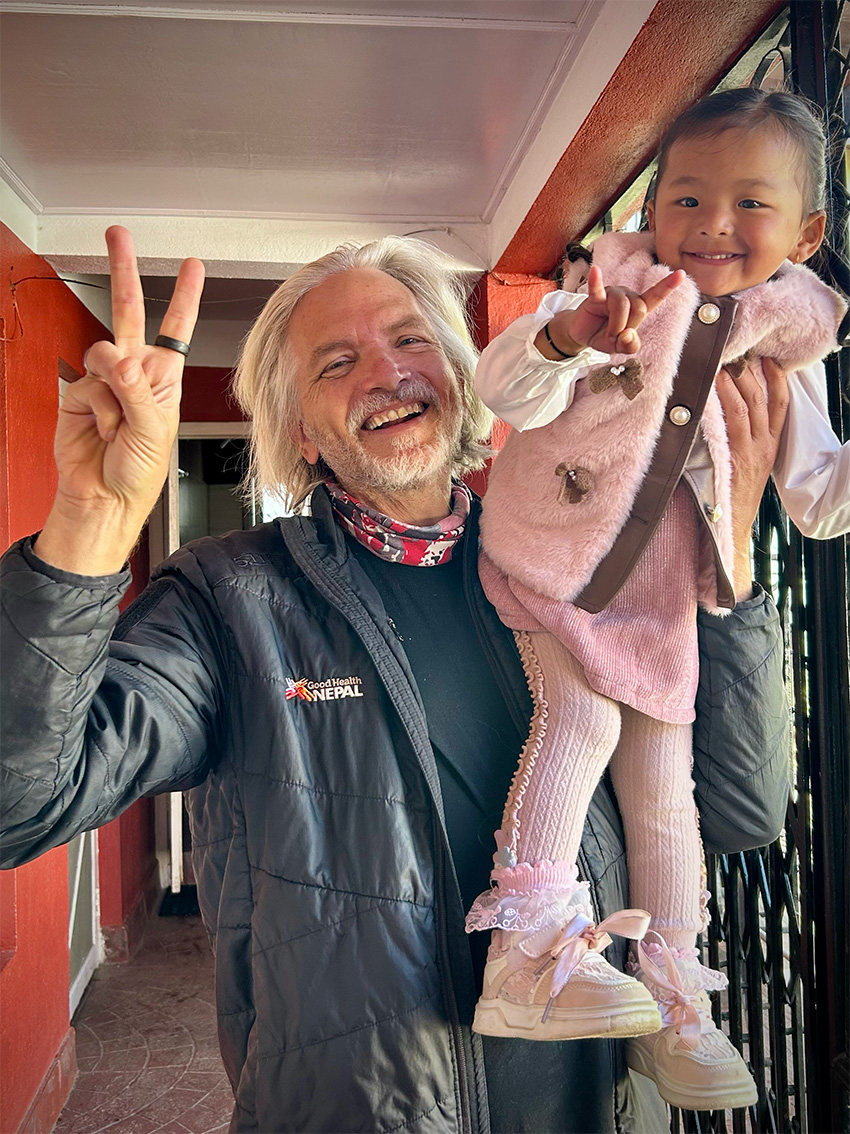

Aavya with her mother and Clinic Director, Sushila Gurung, 2025.

Their lives also intersect with the clinic in ways that go beyond professional roles. Satya and Sushila live on site with their two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Aavya. She moves freely through the clinic, dancing, observing, occasionally demanding attention, and calling me “Andrew Baji” (grandpa). She already shifts comfortably between Nepali and English. Her presence is a daily reminder that this work is not abstract. It is embedded in families, relationships, and future generations.

Aavya with her "Baji", 2025.

Taken together, these stories matter more to me than any single clinical outcome. They represent the gradual transfer of knowledge, responsibility, and confidence. This is what sustainability actually looks like, not replication of a model, but the emergence of capable people who are increasingly shaping the work themselves.

Work Beyond the Clinic

One of the persistent misconceptions about projects like ours is that they operate at the margins of formal health systems. In reality, the opposite has been true. From the beginning, our work has depended on functioning transparently, accountably, and in close coordination with the structures that already exist in Nepal.

Our clinic is regulated and regularly inspected by multiple governing bodies, including the Social Welfare Council, the Nepal Health Professionals Council, the Makwanpur District Health Office, and the Thaha Municipality Health Office. Maintaining these relationships requires ongoing reporting, documentation, and compliance. They are not sustained through visibility or advocacy, but through consistency and trust built over many years.

Physically and functionally, our clinic is co-located with the municipal health post, birthing center, and laboratory. Care is integrated rather than parallel. Patients move between services, information is shared, and decisions are made collaboratively whenever possible. This arrangement allows us to function as part of a local primary care ecosystem rather than as a standalone project, reinforcing the idea that integrative care can complement and strengthen public health infrastructure.

Bajrabarahi Clinic (lower left), Municipal health-post and birthing center (upper right) and Lab (lower right). Photo 2018

At a broader level, our work aligns closely with the concept of Healthy Lifestyle Centers promoted by the World Health Organization. These centers are designed to address the growing burden of chronic disease through community-based, integrated primary care that emphasizes prevention, lifestyle counseling, patient education, and long-term management of conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and musculoskeletal disease. Versions of this model have been adopted in other countries, adapted to local needs and regulatory environments.

While we do not formally use the Healthy Lifestyle Center designation, we function in precisely this way. In fact, to our knowledge, we remain the first and only integrated care clinic in Nepal, one that combines acupuncture, manual therapies, basic medical management, diagnostic reasoning, patient education, and referral within a single, coordinated primary care setting. This integration is not theoretical. It happens daily through shared space, shared patients, and shared clinical responsibility alongside municipal health services.

Our intention has never been to introduce a new label or replicate a predefined model. Instead, we have focused on demonstrating what is possible when integrative care is practiced with rigor, accountability, and respect for existing systems. In that sense, the clinic serves less as a template to be copied and more as a working example, contributing lived experience to an ongoing national and international conversation about how primary care can evolve to meet the realities of chronic disease.

Foreign volunteers come to learn from practitioners and collaborate with our staff.

Volunteers play an important role in this ecosystem, but not in the way many initially expect. The clinic is not designed as a short-term training ground or a place for improvisation without accountability. Volunteers are asked to step into an existing system, to observe carefully, and to work within established clinical and ethical boundaries. For many, this proves to be one of the most valuable aspects of their experience.

Working in a low-resource setting strips clinical decision-making down to its essentials. Without easy access to advanced imaging, specialist referral, or extensive laboratory testing, history-taking, physical examination, and longitudinal observation become central. Volunteers often leave with sharper clinical instincts, a deeper respect for systems-based care, and a clearer understanding of what is truly necessary for effective treatment.

Volunteers and staff conducting outreach health checkup in the village of Kunchal, Spring 2025.

At the same time, this structure makes clear where volunteer involvement must stop. Local practitioners carry responsibility for patients long after volunteers leave. As a result, restraint and humility are as important as technical skill. This boundary, sometimes uncomfortable, is essential to sustainability and patient safety.

Aavya is always up for a photoshoot with volunteers.

There are also persistent challenges. Government policies and regulatory frameworks change frequently, sometimes with little notice. Acupuncture is not formally recognized as a health profession in Nepal, and there are no standardized educational pathways or clearly defined scopes of practice. This creates uncertainty for practitioners, regulators, and patients alike, requiring constant navigation rather than reliance on fixed rules.

Financial sustainability remains another ongoing concern. Capital projects, buildings, equipment, and visible infrastructure are relatively easy to fund. The less visible costs of long-term operation are not. Salaries, medications, utilities, maintenance, training, and administrative work are perpetual needs and far more difficult to support consistently. Balancing ambition with realism is a constant exercise.

None of these challenges are unique to our project. They are the realities of long-term engagement in a complex and evolving health system. What matters is not eliminating uncertainty, but developing the capacity to work responsibly within it, to adapt, remain accountable, and keep patient care at the center of every decision.

In many ways, this work beyond the clinic walls is less visible than individual patient stories or training workshops. But it is here, at the intersection of people, systems, and constraints, that the future of the project will ultimately be shaped.

Returning Home

Each year, when I prepare to leave Nepal, I am aware of the same quiet tension. There is always more work to do, more patients I could see, more conversations I could have, more problems that remain unresolved. And yet, leaving is part of the rhythm that allows me to see the work clearly.

When I am close, inside the clinic, inside a case, inside a difficult decision, the work can feel fragmented. It is made up of incomplete recoveries, careful restraint, incremental progress, and unanswered questions. But with distance, a different picture emerges. I begin to see patterns rather than episodes, relationships rather than transactions, capacity rather than dependency.

When I am in the United States, I teach and I work in private practice. I value both deeply. Teaching keeps me sharp and curious, and clinical practice is grounding and meaningful in its own way. And yet, I am aware that my work in Nepal feels different. It feels more purposeful, more vibrant, and more immediately connected to the lives of the people around me. The stakes are clearer. The impact is more tangible.

Satyamohan and I enjoy a motorbike ride through the local area, 2005.

I am profoundly grateful for the privilege of this experience. While the clinic exists to serve patients and communities, I am under no illusion about where the greatest benefit has fallen. I have learned more here than I could have anticipated, about medicine, responsibility, and the limits of certainty.

Each year, I leave with more questions than answers. That feels appropriate. It is a reminder that this work is not something to be completed, but something to be tended, carefully, imperfectly, and over time. — Andrew Schlabach

Author: Andrew Schlabach, AEMP LAc

Director, Acupuncture Relief Project

Bajrabarahi, Thaha, Makwanpur Nepal